By Ruby Tipple

The V&A’s Marie Antoinette Style exhibition starts with a portrait of the young queen grinning wryly at its viewer. Beneath it sits her mother’s advice in bold black text, given in April 1770, just one month before the fourteen-year-old Marie would be married to the future (and final) French King, Louis XVI. It reads: ‘All eyes will be on you.’

Over two hundred years later, Marie Antoinette (1755-1793) is still drawing our gaze. She has come to represent such a complex, contradictory set of ideals—so much so that ‘Marie Antoinette, the woman’ remains difficult to separate from ‘Marie Antoinette, the icon’. Her name has been repurposed by every generation, often to suit a fictitious, strange, and near-fetishistic mythology that surrounds her.

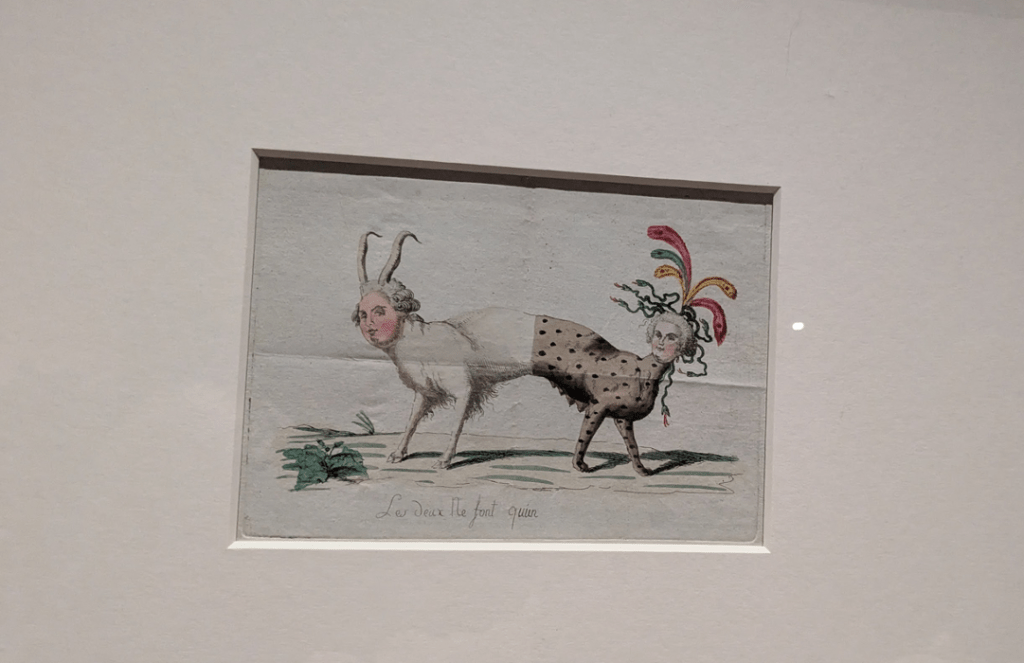

Divisive seems the most appropriate way to describe this cult of personality. The image of Madame Déficit, dressed in extravagant gowns of crepe-de-chine at a time of high unemployment, food shortages and ninety-eight percent poverty, has been symbolic of class protectionism and royal avarice. In Marie, we can find everything ugly and oppressive about the ancien régime. As this new exhibition shows, a wave of hostile satire, infused with misogyny, was hurled toward her in the 1780s. Commentators seemed insistent to degrade her political credibility through assertions of her sexual lasciviousness, economic irresponsibility and bad behaviour. One etching shows her as a monstrous harpy tearing apart the Declaration of the Rights of Man; another imagines her as the new Medusa with snakes in her hair.

© The British Museum

Yet reports of the Queen’s mistreatment at the hands of revolutionary mobs also ignited great waves of pro-royalist sentiment when heard in the English Parliament. In his 1790 Reflections on the Revolution in France, Whig MP Edmund Burke wrote an account of the October Days of 1789, a series of marches on Versailles Palace by women which forced the Royal family to return to Paris. Burke emphasised the near-fatal raid upon Marie’s bedchamber, presenting an image of a defiled young woman. This was a canvas upon which monarchists could support the political orthodoxy that many at the time hated her for.

Yet aspects of her image seem completely stripped of their political connotations. She remains considered as a strange sort of teen-dream it-girl—commercial, sassy, iconoclastic, controversial, but above all, exciting. Madonna dressed as her to perform the hit song ‘Vogue’ at the 1990 VMAs. Feminist auteur Sofia Coppola chose her as the chic emblem of misunderstood girlhood in her stylish, punk-soundtracked 2006 Marie Antoinette. Kate Moss posed as her in a 2012 photoshoot for American Vogue, dripping in turquoise regalia by Alexander McQueen and with a look of glacial imperviousness to match. She turns away from the viewer, instead gazing adoringly at the finery she is surrounded by at the Imperial Suite of the Ritz in Paris, with its pastel-hued Louis XVI-style interiors.

© Tim Walker Photography

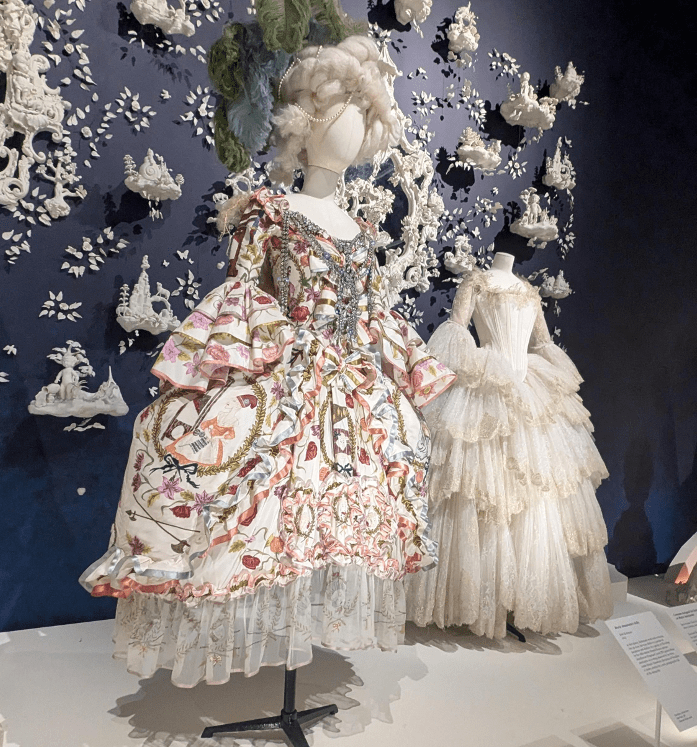

Marie’s influence on the fashion industry remains extensive, as the final third of the exhibition proves. The show’s last rooms display how her trendsetting style has been variously translated and reinterpreted by fashion houses including Dior, Vivienne Westwood, Chanel and Moschino. A giant television screen in the final room presents a dazzling compilation of the catwalks and photoshoots that owe their extravagance to the striking image of the French queen. Perhaps the fusion between Marie and her ‘fashion icon’ status, though, is most obviously realised before the exhibition even starts, through shoe designer Manolo Blahnik’s decision to sponsor it. As a plaque explains: ‘The partnership reflects Manolo Blahnik’s enduring admiration of Marie Antoinette, her lasting charm, and the profound impact she has had on his designs.’

Here lies the unresolved tension that defines the V&A’s Marie Antoinette Style. Introductory text sets out the exhibition’s desire to provide some sort of answer to the all-important question: who was the Queen beneath her image? Yet, the exhibition never quite gets to the heart of it—still too enraptured by this fashionable invention of ‘Marie’, not quite doing justice to the real woman or her complex political legacy.

Rightly, what the exhibition makes apparent, however, is that Marie was victimised by a patriarchal system. Much of it focuses on her teenage years as a child bride, with her childhood pursuits of music, for example. Even in rooms filled with diamond necklaces and the ostentatious fashion trends she inspired, it remains difficult to forget her youthfulness and vulnerability. The jewellery she wears is evidently expensive but is seen in miniature—necklaces made to adorn the thin neck of an adolescent. The worn, beaded pink silk slippers belonging to Antoinette are another apt example, eerily small and childlike in their display box.

She was a victim, too, in lacking much political power in the late years of her reign—something most acutely understood in the room dedicated to Marie’s execution. Here, the music stops and her deathbed relics sit in blood-red lighting. The reported guillotine blade used for her execution, a Madame Tussauds death-mask, and a medallion containing a lock of her dark blonde hair, intertwined with her son Louis-Charles’, are some of the items on display here. The only preserved item of clothing actually worn by Antoinette throughout the entire exhibition is her thin, plain white chemise, mounted on the wall using specially-designed magnets to make it appear like a ghostly apparition.

© V&A Museum, London

The inclusion of her final diary entry is the last relic of the room. At 4.30am, before the dawn of her execution, it reads: ‘My God, have pity on me! My eyes have no more tears to cry for you my poor children; adieu, adieu!‘ Here, at its most obvious, is the enduring cultural image of Marie stripped bare. The popular cake-eating, ‘love-to-hate-her’ reputation, seems disconnected from her life’s visceral conclusion.

It is a wasted opportunity, then, to swiftly end the exhibition with a glittery return to a more palatable interpretation of Marie in line with the ‘style icon’ image which flattens her legacy. An opulent room filled with dresses, like John Galliano’s 2000-2001 ‘Angie’ gown from the Fetish collection and Jeremy Scott’s ‘Let them eat cake’ gown from Moschino’s 2020-21 collection, leaves a sour taste in one’s mouth by using history to justify the profit-driven, unsustainable fashion production of the present. It doesn’t show Marie as a complex and politically-fraught figure in the way the exhibition claims, in its opening, that it will do. By the end, we seem to have backtracked on any empathy extended to the woman behind such an elusive and multifaceted image. She is, instead, reduced to a caricature, celebrating commercialised royalty as if it were her most important historical contribution.

© V&A Museum, London

Another uncritical inclusion is the exhibition’s integration of ‘scent as education’, where the smells of eighteenth-century Versailles are brought to life in perfumed busts of the queen. The concept feels too close to an over-indulgent emulation of eighteenth-century French royalty, a group whose luxuries were structurally dependent on severe social inequality. Indeed, charging a £25 entrance fee to smell the lost fragrances of a royal palace crosses the line from historical education into problematic levels of imitation. Today’s political climate, careening towards new-found levels of economic suffering and wealth disparity, makes this feature appear even more misjudged.

There is also little ink expended on the link between the exorbitantly priced objects that upheld her public image and French colonialism, missing an opportunity to explore an important and often sidelined dimension of Marie’s style: what funded it.

Throughout Marie Antoinette Style, we are reminded of how each generation has taken the symbol of ‘Marie Antoinette’ to suit the conditions of their times. What about today, then? How should we see her in her first UK exhibition?

We have the responsibility to portray Marie as more than just the original ‘Queen Bitch’ of the eighteenth-century, a trap which the V&A’s exhibition too often falls prey too. In failing to understand her outside this fashionable caricature—one which, admittedly, seems to guarantee ticket sales due to the contemporary appetite for visual splendour—we not only rob ourselves of untangling her political and colonial legacy, but also, as the exhibition shows at its strengths, we obscure the real woman beyond the aesthetic icon.

The V&A exhibition tells us that Marie never said ‘let them eat cake’ as her last words. Let’s stop celebrating the version of her that would have.

© V&A Museum, London

Marie Antoinette Style at V&A South Kensington, London, closes Sunday 22nd March 2026

Weekday tickets £23

Weekend tickets £25

All photography courtesy of Ruby Tipple

References

Castle, T. (1992). ‘Marie Antoinette Obsession’. Representations.

Ferriss, S., & Young, M. (2010). “Marie Antoinette”: Fashion, Third-Wave Feminism, and Chick Culture. Literature/Film Quarterly, 38(2)

https://www.vogue.co.uk/article/inside-v-and-a-marie-antoinette-style