By Zoe Wilkinson

Art gave Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun access to the world of the aristocracy. From Marie-Antoinette to the Russian court, her portraits were central in representing women of the era. There is a sense of nostalgia and solidarity in Vigée Le Brun’s comment that ‘women reigned then; the revolution dethroned them’. The reality, however, was far more contradictory. Scandal was inevitable where women and their images were concerned, making life and art a series of negotiations. Unpicking these negotiations is a revealing process: behind them, we find Vigée Le Brun’s commitment to artistic ‘likeness’.

To be female and a recognised professional artist remained something of a contradiction when Vigée Le Brun began her career. Despite becoming a financially independent artist at only fifteen years old, in May 1783 she was one of only four women allowed places in the Académie Royale, the Ancien Régime’s most established art institution, and even then, her admission had to be pushed through by Marie-Antoinette. It was at this time that Vigée Le Brun became more closely associated with the French Queen, a relationship that would prove to be a double-edged sword for her reputation.

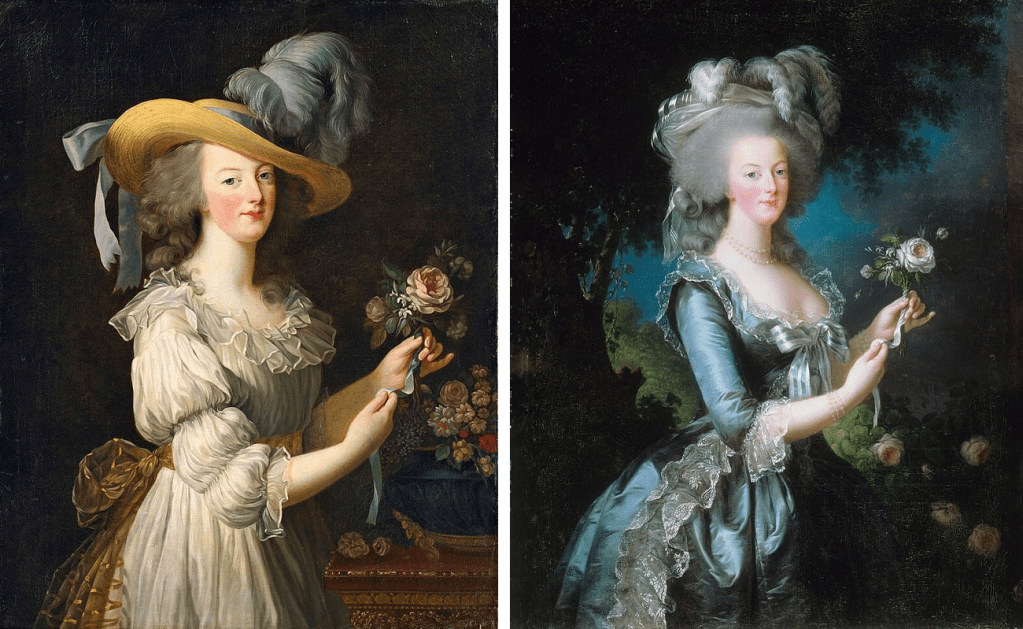

A 1783 portrait known as ‘Marie-Antoinette en Gaulle’ (or ‘La Reine en Gaulle’) quickly became the subject of a scandal. Vigée Le Brun depicts the Queen in one of the simple, muslin dresses she had taken to wearing since her first pregnancy. The dress is billowy and unstructured, the neckline hemmed with ruffles, and the waist lightly tied with a sheer golden sash. The dress—topped off with a straw hat—feels relaxed and pastoral, but the plain black background ensures that the figure is striking, even vaguely sombre, with the dark hues more akin to Dutch rather than French paintings. The artistic establishment baulked at the informality of the Queen’s dress, which resembled an undergarment. Vigée Le Brun was acutely aware of the risk the painting posed to her professional reputation. Deciding to put her career first, she submitted a new and altogether more acceptable painting to the Académie. ‘Marie-Antoinette à la Rose’ depicts the Queen in a formal blue silk dress and in front of a classical background. With looser brushwork, Antoinette’s face is less defined; it is soft and more saturated. Comparing the two portraits, it is evident that the truthfulness of Vigée Le Brun’s original representation appears to have been lost.

In this first portrait, we see why Marie-Antoinette considered Vigée Le Brun’s portraits ‘the best likenesses [rassemblant] which have ever been done [of me].’ It is difficult to say whether the idea for the simple muslin dress came from Marie-Antoinette (a conscious self-fashioner) or Vigée Le Brun (known to manipulate the outfits of her sitters), but we can be sure that the style, which renders Antoinette’s face with as much physicality and precision as her dress, was key in creating a truthful ‘ressemblance’, or ‘likeness’. We should not see the repainting as a sacrifice of ‘ressemblance’, but as a canny compromise to preserve Vigée Le Brun’s artistic career. It draws our attention to the conflict between the worlds of the private—the muslin dress, the legible face—and the public that Vigée Le Brun felt so keenly.

Such tension between the private and the public is necessarily a consideration of portraiture, but was likely to be felt more acutely by Vigée Le Brun because she was a woman. The 1787 exhibition of her first ‘Self-Portrait with her Daughter, Julie’ created a second scandal: through her proud smile, a glimpse of the artist-mother’s teeth could be seen. Teeth were shorthand for the bawdy and licentious: more fitting for a Franz Hals tavern scene than for the High Rococo styling of the French court. To the modern eye, the painting is evocative of a selfie: Vigée Le Brun’s gently smiling face tilted towards the serene, half-turned head of her young daughter. The smile is not a smile of licentiousness but a public display of the pride and joy found in such a private, intimate scene. Vigée Le Brun was reinventing the traditional associations of this kind of smile—which, we might note, is still a long way from being a toothy grin—by demonstrating its place in the emotions of motherhood. In turn, she transposed the facial expressions of private spaces into the public space of the portrait. Her sense of ‘ressemblance’ was firmly grounded in the material expression of emotional realities: ‘likeness’ could be idealistic so long as it contained truth.

Due to her close association with Marie-Antoinette, Vigée Le Brun was forced to flee France at the advent of the French Revolution in 1789, living in artistic exile and travelling across Europe. The freedoms this offered allowed her to become more skilled in negotiating idealisation and naturalism in her portraits. Her ‘Portrait of Countess Golovina’ (1797-1800), now housed at the Barber Institute in Birmingham, demonstrates this balance: the eyes are unrealistically large but unequivocally mesmerising, the folds of her shawl perfect and vivid, the hair somewhere between natural and wild. The painting is idealistic, but it is also strikingly direct. The Countess seems at once otherworldly, enchanting us with her eyes and smile, but also physically embodied through luscious brushstrokes. Lines under her eyes create a bulging effect; the Countess’ nose is distinctive, even rather lumpy in shape. Art historian Kathleen Nicholson has drawn attention to ‘Vigée Le Brun’s awareness of her female subject’s affectations and her ability to flatter them’, but here we see likeness more than flattery. Vigée Le Brun is working a strong sense of the individual and their unique physicality into her painterly concept of the beautiful.

Vigée Le Brun was a monumental figure in the world of portrait painting. Joshua Reynolds considered her one of the greatest artists of the age, even stating that he couldn’t match the artistic achievement of her 1786 portrait of the Comte de Calonne. And yet it was only in 2015 that she had an exhibition dedicated to her in France. We must continue to rediscover Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, both as an artist and as a woman; in doing so, we find scandal, rebellion, ‘ressemblance’ and extraordinary paintings.

References

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Marie-Antoinette en gaulle, 1783, oil on canvas, 92.7 x 73.1cm, National Gallery of Art, Washington.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Self-Portrait with her Daughter Julie, 1786, oil on canvas, 105 x 84cm, RMN Grand Palais, Paris.

Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun, Portrait of Countess Golovina, 1797-1800, oil on canvas, 83.5 x 66.7cm, Barber Institute of Fine Arts, Birmingham.

Larkin, T. Lawrence, ‘‘Je ne suis plus la Reine, je suis moi’: Marie-Antoinette at the Salon of 1783’, Aurora: The Journal of the History of Art, 4 (2003), 109-134.

Nicholson, Kathleen, ‘Vigée Le Brun [Vigée-Le Brun; Vigée-Lebrun], Elisabeth-Louise’, Grove Art Online (2003), <https://www.oxfordartonline.com/groveart/view/10.1093/gao/9781884446054.001.0001/oao-9781884446054-e-7000089458> [accessed 8 Oct 2024]

Schofield, Hugh, ‘A delayed tribute to France’s most famous woman’, BBC News (2015), <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/magazine-34340907> [accessed 19 Oct 2024]

Sheriff, Mary D., ‘The Cradle is Empty: Elisabeth Vigée-Lebrun, Marie-Antoinette, and the Problem of Invention, in Women, Art and the Politics of Identity in Eighteenth-Century Europe, ed. by Melissa Hyde and Jennifer Milam (Abingdon: Routledge, 2016), pp. 164-187.