by Elizabeth Mazzola

Unlike Shakespeare’s Viola or Spenser’s Britomart, the travels of 16th century poet and maidservant Isabella Whitney were real and transpired without the benefit of any disguise. Nor were Whitney’s travels temporary ones, designed to quickly land her a husband or install her elsewhere, with the life lessons acquired on the run ultimately shelved wherever home is stationed when it’s finally reached. Neither migrant nor fugitive, Whitney makes her home in a thoroughfare, telling us about London’s attractions and pitfalls in her 1573 Wyll and Testament, a poem about leave-taking that also shows its readers how to stay put. Although this poem describes Whitney’s departure from London in terms of a metaphorical death and burial, Whitney doesn’t emphasize this escape but instead prolongs the journey. She carefully tells us about where she’s been as well as what the chance to move about so freely has meant for her.

Whitney is the first professional woman writer in England who published and circulated her work in print, but the fact that her example involves her eviction sometimes complicates her message. The Wyll and Testament has been read as the bitter farewell of a household servant abruptly discharged from her post. Some critics, like Wendy Wall, liken Whitney’s complaints when she’s cut off from the pitiless city’s riches to those of a Petrarchan lover rejected by the indifferent object of her desire. The speaker’s situation is a dire one, and maybe staging her own death supplies the only way to retain some control, given her lack of a post or husband or any obvious reason to stay. But the opportunity which Whitney takes to fashion her ‘will’ plays with this power to turn loss into gain. The speaker’s inventory of London’s treasures with specific instructions for bestowing them involves a complex pose that is at once satirical and ironic, spiritually uplifting and crassly reductive. ‘I Whole in body, and in minde / but very weake in Purse’ is how she introduces herself, before moving on to distribute goods she’s never owned, sharing riches long withheld from her.

The degree of detail and careful attention to specific sites, streets, and merchandise emphasize the speaker as a long-time denizen of London. She is shrewd enough to know what to expect and when to leave, as well as how one might stick around: loitering but not idling, finding safety and security in this environment. Rarely does Whitney mention the companionship of ‘my Friends’, so presumably her clear familiarity with this setting has been acquired on her own over a considerable period of time, allowing her to look, gape, and stare, even though no one seems to see her. No one greets or succors her. Instead, the speaker notices many people like her, equally determined to ride out rough times. If London is filled with things she will ‘willingly’ leave behind—including ‘foode’ and ‘Plate to furnysh Cubbards with,’ ‘Wollen’ and ‘Linnen,’ ‘Bootes, Shoes’ and ‘Beds’–’Betweene’ its ‘fayre streats’ there are ’people goodly store,’ whose “keeping craveth cost.’ Alongside Whitney’s list of London attractions is an accounting of these human expenses.

But we might also read Whitney’s Wyll and Testament as something of a survival guide, a toolkit or crib sheet for urban dwelling in the shadows, designed for other single women similarly situated. Think Richard Bolles’ famous handbook for adulthood What Color is Your Parachute?, without the high-tech launching equipment–or, better yet, HBO’s Sex and the City, with fewer shoes, and more of a shoestring.

Whitney’s speaker occupies public space invisibly but successfully, undamaged by the exposure, enlightened by the spectacle. It seems remarkably easy for her to see everything in this space; even London’s Tennis Courts and fashionable shops aren’t closed off to her, and dreary spaces receive her attention, too. Of course, we hear about ‘Braue buildyngs rare’ like St. Paul’s Cathedral, but rather than being presented as a scene of piety or somber communion with God, ‘Paulles’ provides the location for book stalls and booksellers, hustling authors, and hungry readers. The rest of London’s streets and stores extend this picture of a busy marketplace. Wall comments on how Whitney’s refashioning of the language of legacy ‘acts as a complex form in which a provisional self-authorization is made possible’, but many other people are revealed by Whitney’s ‘self-authorization’ too, including women ‘lyke me,’ she says, ‘and other moe.’

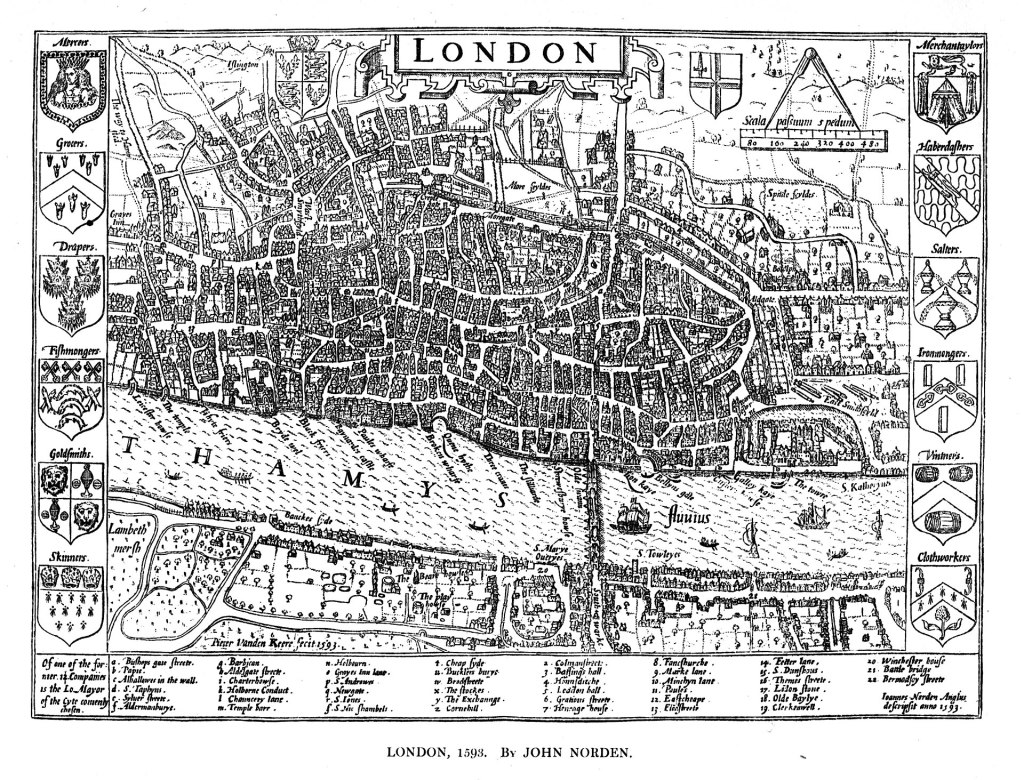

Stefani Brusberg-Kiermeier sees Whitney’s efforts at seeing and sharing as bolder still, proposing that Whitney claims ownership of the city and renders early modern commercial London ‘in loving detail’ while ‘partaking in the new science of topography’. Yet Whitney’s speaker also obliquely points out places to hide, sites which a regular map might miss, and resources like pawnbrokers who are available to those down on their luck or hoping for a way out of trouble. Maybe in providing a ‘certain hole’ for unlucky women, these secret or shadowy places of relief keep women solvent, intact, undetectable, and ‘whole.’ ‘[O]ft’ the speaker’s walks have also taken her past dangerous settings like Bedlam and Ludgate where punishment is administered and discipline enforced. In these instances, Whitney’s poem guides her readers around and past treacherous sites where women might get lost. Other danger zones like the Stocks or Bridewell (where women might be imprisoned, as Alicia Meyer explores, for sex work or unplanned pregnancies, as well as for vagrancy and unemployment) reinforce the picture of a ‘cruel’ urban setting which Whitney successfully navigates. Her map also encodes other places of ‘little ease’ and assistance for women who need or want to stay with references to ‘my Printer.’ This shout-out to Whitney’s associate Richard Jones supplies an important connection for other emerging writers, given Jones’ reputation for publishing cheaply printed materials like pamphlets, ballads, and verse miscellanies. Jones knew the book business and how to stimulate this market, and Michelle O’Callaghan’s investigation of Whitney’s decade-long working relationship with Jones suggests he had figured out exactly how to to reach a ‘rapidly expanding readership’ in London. Those readers consumed a range of texts which frequently described love and life in London and eagerly paid for stories about figures like themselves, young people moving through and around London.

Whitney includes other resources for young women which might help them make money, sell their wares or their labor, or remedy medical conditions, like an unwanted pregnancy. ‘[W]ith Banquets in their Shop’, ‘[A]Poticaries’ could supply abortifacient herbs to enable contraception, stimulate menstruation, or provoke a miscarriage. Maybe the reference to ‘cunning Surgions’ who do not cut or sew but instead use ‘Playsters’ to fix boisterous, bleeding ‘Roysters’ likewise hints at additional cures for female maladies, including tears to other bodily walls. The list of London’s suppliers and merchandise not only suggests how women might sustain themselves in an often-unwelcoming city, but even maintain some control over their bodies there.

In other words, while Whitney’s poem describes her leave-taking, it also suggests how other ‘Girles’ could be ‘set’ ‘aflote’ and allowed to remain in London. Alternating among the perspectives of savvy tourist, moral guide, and street-smart hustler, Whitney’s speaker continually recognizes that not everyone can leave or has somewhere else to go. Indeed, this group of stragglers, aspirant poets, and balladeers is a large one. If we conclude that the audience Whitney and her Printer strive to reach was mostly comprised of people who had somehow failed—rogues and prostitutes, criminals and con-artists–then we would overlook an enormous collection of ‘unsettled’ people like apprentices, servants, and other young people who were figuring out how to navigate new lives in new urban centers. Some of them might be planning–or find themselves needing–to leave London, but some would want to stay or even need to hide (perhaps from a creditor). We can also read Whitney’s Wyll as providing a catalog of short-term solutions and relatively easy fixes (like finding a ‘ritch’ ‘Widdoer’) for the problems posed in this crowded, busy, urban world.

Paying more attention to how Whitney learned about an underworld of side streets and side hustles, temp work, and valuable resources might also help us to imagine other survivors and where they might be. To be sure, Whitney’s earlier poetry addresses a similar audience of vulnerable young maids, warning them about male flattery and deceit in a Sweet Nosegay, which offers another set of herbal remedies for this group of readers (see Wall). But in her Wyll and Testament, the instructions are less about repelling amoral men, and more about simply staying alive in a tricky world filled with opportunity and punishment, ‘infection’ and relief. Early modern good girls, and bad ones, tended to spend most of their time locked up in one way or another, but Whitney uncovers a third group who might successfully manage outdoors with the advice she shares. Their ranks are actually legion, and among them we can include Marie de France’s heroines, who often move about secretly and skillfully, as well as Milton’s Eve, who dreams of flying over Paradise. Maybe Margaret Cavendish’s Empress in the 1666 Blazing World belongs here, too. Able to leave and return to her homeland at will, the Empress’s mobility signals her sovereign power and imperial rule, and it also illustrates a self like Whitney’s, in command of what it needs as well as what it can leave behind.

References

Brusberg-Kiermeier, Stefani. “Isabella Whitney and London.” The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Urban Literary Studies Ed. Jeremy Tambling (2022): 971-978. https://link-springer-com.ccny-proxy1.libr.ccny.cuny.edu/content/pdf/10.1007/978-3-319-62419-8_300359.pdf?pdf=core. Downloaded 26 August 2023.

Meyer, Alicia. “Criminalizing Pregnancy before Dobbs: The Case of Elizabeth Brian at Bridewell Hospital.” Synapsis: A Health Humanities Journal (2022) https://medicalhealthhumanities.com/2022/06/30/criminalizing-pregnancy-before-dobbs-the-case-of-elizabeth-brian-at-bridewell-hospital/ downloaded 27 August 2023.

O’Callaghan, Michelle. “’My Printer must, haue somwhat to his share’: Isabella Whitney, Richard Jones, and Crafting Books.” Women’s Writing 26, 1 (2019):15-34.

Wall, Wendy. “Isabella Whitney and the Female Legacy.” English Literary History 58, 1 (1991):35-62.