By Ana Olendraru

Comic artistry is an area often perceived and marketed as primarily male. Popular media presents comic books and their characters as a form of art addressed to young boys or to the stereotypical ‘loveable nerd’, most often a man (e.g. The Big Bang Theory, one of the most popular TV shows with an average of 18 million viewers and a span of 10 seasons so far). It might then come as a surprise to many that one of the trailblazers in graphics, picture-making, and comics was Marie Duval, an illustrator working for a two-penny magazine in Victorian England.

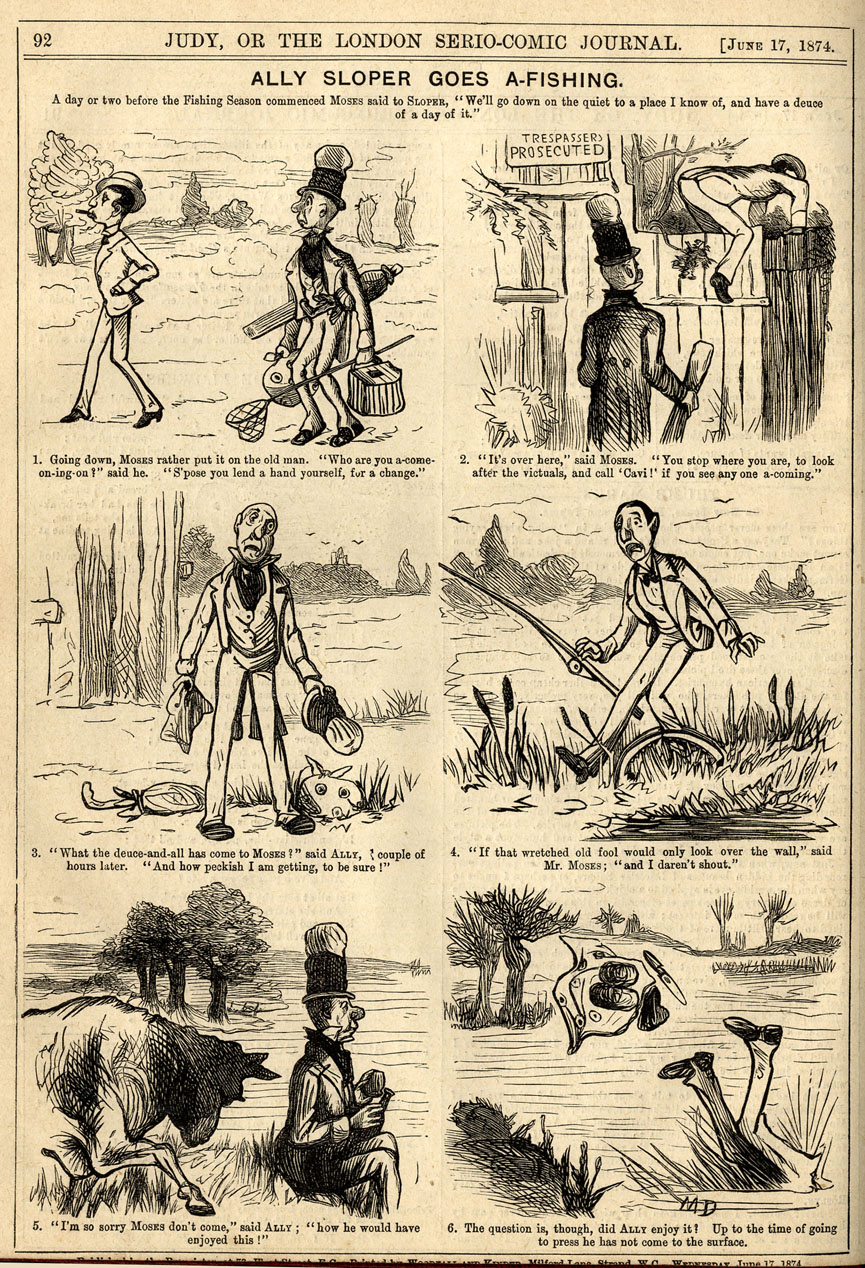

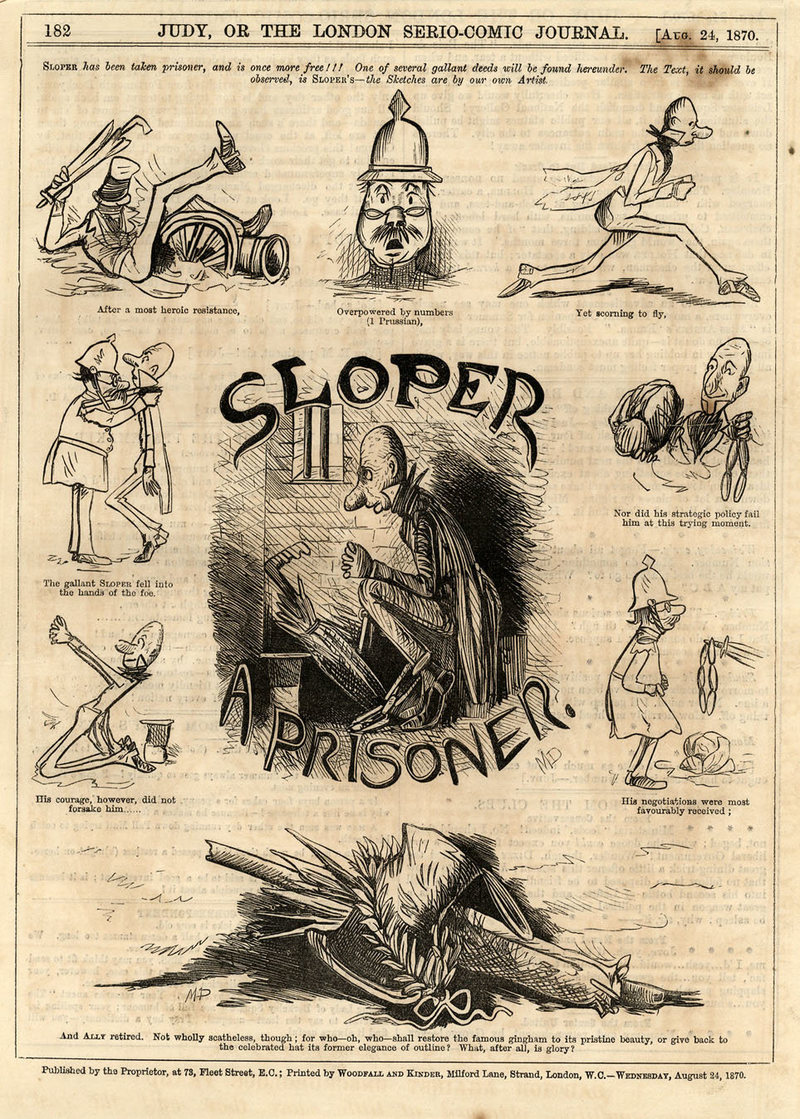

The character of Ally Sloper, the ruddy-cheeked, tulip-nosed, working-class man doing his best to escape his creditors first appeared in Judy magazine under the hand of Charles H. Ross. He was discontinued but reappeared years later with new attributes, new companions, and weekly adventures, reaching unparalleled popularity. Although he remained attributed to Charles H. Ross, Ally Sloper’s new persona was now created and illustrated. by his wife, former actress Marie Duval who signed all her drawings ‘MD’ or ‘Marie Duval’.

‘Ally Sloper goes Fishing’ Judy Magazine June 17th 1874, signed MD

It seemed more likely to the public that the already established illustrator and editor of Judy Charles H. Ross was using his wife’s name, than that Duval could have created the new world of Ally Sloper, the character regarded as the first recurring comic strip character, herself. Art critic David Kunzle sees this as a particularly good example of the tendency to ascribe work done by a wife to a professionally established husband and to see women artists as appendages to male innovators rather than as innovators themselves. This leads to the erasure of the work of women artists: Duval’s contribution was erased both by the attribution of her work to her husband and by the post-Duval reincarnations of Ally Sloper (e.g. W. G. Baxter’s Ally Sloper).

Caricature, and journalism in general, was a male-dominated field in Victorian England as ‘women’s nature’ was considered antithetical to the “aggressive polemical and critical nature of so much journalism in general and caricature in particular” (Kunzle, 1986). It is in this context that Marie Duval laid the foundation for comic strips as we know them today. Although long-denied to her, she is now given credit for the development of the first regular continuing comic strip and cartoon character in England to attain an unparalleled level of popularity (it was later commercialized and appeared on snuffboxes and doorstops) and for the expansion of the language of graphics in the 20th century.

In Victorian England, the few women who drew were expected to illustrate sophisticated and elegant subjects as opposed to comical caricatures. Women were breaking into the fields of illustration and visual journalism, many having received formal training. These classically trained artists drew upper-class subjects in a graceful style. Duval had no formal training, instead using her experience as an actress playing the role of Jack Sheppard, a character similar to Ally Sloper, to depict working-class subjects. Her drawings are filled with depictions of physical movement, distinguishing them from the often static comics of the era and showing her stage experience. In her book English Female Artists, Ellen Clayton describes Duval in a short section entitled ‘Humorous Designers’. At the time, wit was the female attribute and humour the male one. Women were expected to limit themselves to – or believed to only be capable of – the kind of witty repartee one might find in a Jane Austen novel. They could amuse and entertain but coarse or crude jokes, and the physical or critical humour found in caricatures were off-limits for them. Duval’s style is the only one to be considered “truly humorous” while the other artists in the section are deemed to be merely “witty”, as was suitable for women of the time. Duval was therefore not only an exception among illustrators of the time, being a woman, she was also an exception among the small class of women illustrators.

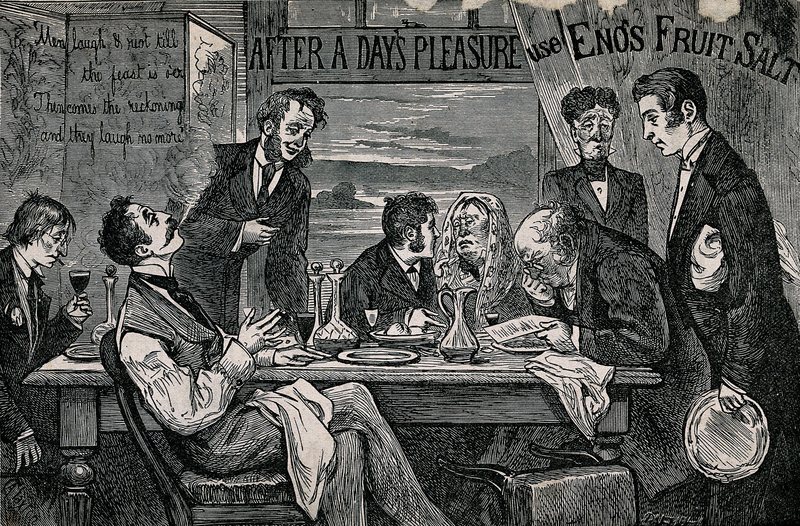

‘Sloper: A Prisoner, Judy Magazine (August 24th, 1870), signed ‘MD’

The depiction of a working-class character who tries his best to make money by doing the least work possible further distinguished Duval from her male and female counterparts as she became a satirist of the Victorian work ethic. While bourgeois culture of the time, in order to justify looking away from the hardships of the working-class depicted it as either unhappy but deserving of its situation caused by its own laziness alone or jolly and satisfied to play its necessary part in the natural order of society, Duval depicted a character in ragged clothes whose nose was flushed with drink and whose weekly adventures focused on cheating his creditors; being all at once lazy and unsatisfied with his status, but oftentimes jolly, sympathetic and pictured as being justified by his circumstances, Ally Sloper defied both stereotypes of the working-class. Duval’s comics depicted the notion of institutionalized cheating that later inspired Charlie Chaplin’s ‘tramp’ character and W.C. Fields: because the working-class is constantly cheated by the upper-class, it survives by cheating it back. Thus, Duval’s Ally Sloper adapts to the system he is forced to work in by attempting to take advantage of it; the inspiration is visible in Chaplin’s character, who breaks windows in order to be later paid to fix them in The Kid, combining humour with criticism of societal norms. The success of this humorous but nonetheless powerful rejection of the bourgeois model of the working-class is proved by the fact that Ally Sloper reached popularity among a mainly working-class audience.

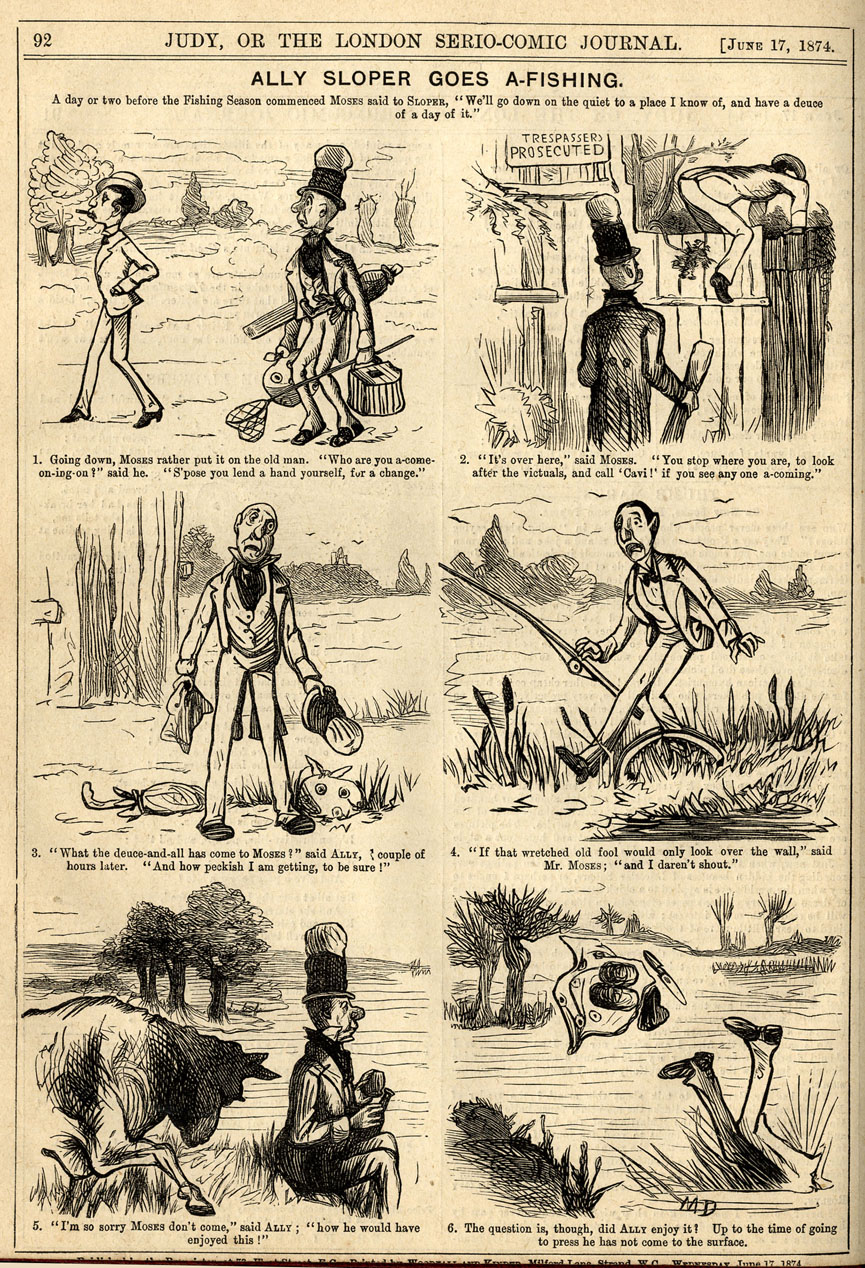

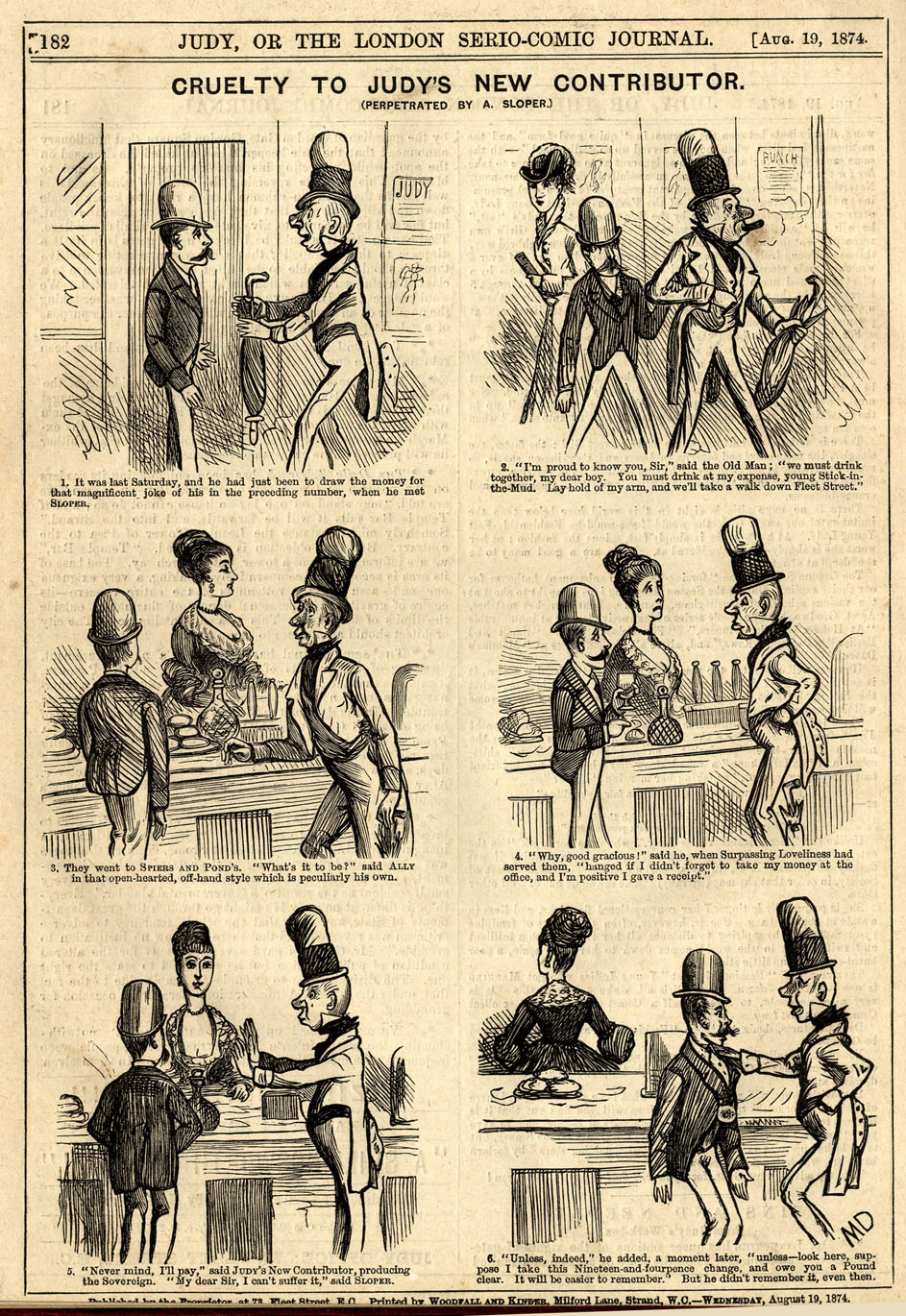

‘Cruelty to Judy’s new contributor (perpetuated by A Sloper), Judy Magazine, August 18th 1874, signed MD

David Kunzle takes the interpretation of Duval’s work even further by tying her depicted rejection of upper-class culture to her rejection of the maleness and conventions of the field she was working in, not only by the simple fact that she was a woman but also by the fact that she engaged in political discourse through her satire: “… one might speculate on the significance of the fact that Ally Sloper, the ex-proletarian, social primitive and lower-middle-class impostor, was popularized by a woman, one of the gender proletarianized and primitivized (not to say infantilized) by exclusion from male-dominated society. And there is a subversive element to her style of graphic experimentation, which suggests a happy aesthetic frivolity and disrespect for academic norms. This, given the characterization of Ally, may be extrapolated as disrespect for the conventional (male) view of life and work.”

Judy itself tended towards a feminist platform, favouring cartoons showing poised women fending off conceited men, but Marie Duval embodied this feminism not by depicting female characters but by rejecting the male upper-class culture which permeated the field she worked in and her every day life.