By Henrietta Heald

What was a girl to do in the year 1900 if she wanted to become an engineer? It helped to have a father called Charles Parsons, whose creation of the steam turbine had marked him out as an inventive genius – to say nothing of a star-gazing grandfather who had built a six-foot-diameter telescope, the largest in the world for more than 70 years. The ancestral astronomer was William Parsons, third earl of Rosse, president of the Royal Society from 1848 to 1854.

Perhaps even more important was the legacy of a grandmother, Mary Rosse, who had herself been an astronomer and engineer, as well as a pioneer of early photography, and the influence of a mother who would become one of the foremost campaigners in northeast England for women’s rights.

Rachel Parsons was 15 years old at the dawn of the 20th century. From early childhood she had shown an aptitude for science and was never happier than when helping her father in his workshop. Rachel and her brother, Tommy, grew up in Northumberland and spent their days roaming the moors or crashing through the waves in increasingly faster boats. Their father, meanwhile, was building up a highly successful industrial concern at Heaton, on the eastern edge of Newcastle upon Tyne.

Rachel had been aboard her father’s legendary Turbinia at the Spithead Navy Review of June 1897, celebrating Queen Victoria’s diamond jubilee, when the speed of the little ship amazed the watching crowd, including the Royal Family, Lords of the Admiralty and visiting foreign dignitaries. Built as an experimental vessel, Turbinia was the first ship to be powered by Charles Parsons’s steam turbines. Much faster than all other seaborne craft of the time, she appeared unannounced at Spithead and raced between the lines of majestic ships, steaming up and down in front of the princes and admirals, and deftly evading a Navy picket boat that tried to stop her. It was a publicity stunt that alerted the world’s decision-makers to the potential of the steam turbine and set the standard for the next generation of super-vessels, including dreadnoughts and transatlantic liners such as Mauretania, Lusitania and Titanic.

Rachel Parsons had no desire to follow the conventional paths expected of a young lady. On the contrary, she was hungry for the kind of robust education offered by English public schools like Eton and Winchester – then, as now, open only to boys. In 1900, Rachel arrived at Roedean, a girls’ boarding school near Brighton, founded by Penelope, Dorothy and Millicent Lawrence. In the mid-1870s, Penelope Lawrence had been one of the earliest students at Newnham College, Cambridge, where she read Natural Sciences.

While at Roedean, Rachel indulged her love of scientific exploration and discovery under the inspirational guidance of Penelope Lawrence. This prepared her for another great intellectual adventure. In 1910, Rachel Parsons became one of the first three women to study Mechanical Sciences at Cambridge. Following in Penelope’s footsteps, her chosen college was Newnham.

At Cambridge, Rachel consolidated the engineering skills she had absorbed in her father’s workshop and added theoretical knowledge to practical experience, but, in common with other female students at the time, she was barred from becoming a full member of the university, which made her ineligible for a degree.(1)

Rachel was in northeast England when war broke out in August 1914. When her brother joined the Royal Field Artillery the following month, she took his place as a director on the board of the Heaton Works. For much of the war, Rachel had a hands-on role at the works, where she took charge of the growing cohort of female employees, hired to take the place of fighting men. Among other crucial jobs, the women at Heaton made the searchlight equipment to produce ‘the beautiful beams of light travelling over the sky in the search for Zeppelin and aircraft’.(2)

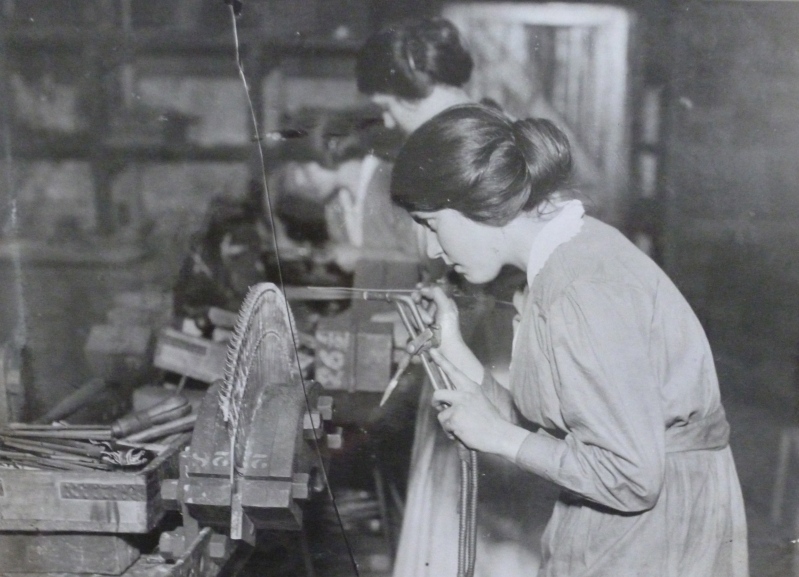

By the second year of the war, the need for more munitions workers had become acute. More than two million men had joined the armed forces and the military authorities were pressing for more, while a huge increase in the supply of war materials was urgently required. When a Ministry of Munitions was established under David Lloyd George, Rachel Parsons joined the training department, instructing thousands of women in the factories of Tyneside to perform a multitude of mechanical tasks. The women did everything from assembling aircraft parts to installing electrical wiring on battleships. While some excelled at intricate tasks requiring the highest degree of precision and accuracy, others were involved in physically demanding aspects of shell production, ‘working hydraulic presses, guiding huge overhead cranes, lifting the molten ingots, fitting the tools in the machines, inspecting and gauging, painting the finished shell cases’.(3) Some 800,000 women were recruited into Britain’s engineering works during the war, reflecting a much larger increase of female employees than in any other trade or profession.

Lloyd George, meanwhile, had struck an infamous deal with the engineering trade unions. To persuade them to accept the ‘dilution’ of labour – the entry of unskilled workers of both sexes into jobs traditionally held by skilled men – he agreed that, when the war ended, all women in engineering would be obliged to give up their jobs to men unless they worked for firms that had employed women before the war. This became law in 1919 as the Restoration of Pre-War Practices Act.

Several important victories in female emancipation were achieved at this time. Women over 30 were given the vote; those over 21 were allowed to stand for Parliament; and the Sex Disqualification (Removal) Act allowed women entry to certain professions, such as medicine and the law. But those who wanted to be engineers – even those who had made victory possible – found doors slammed in their faces. The trade unions were intransigent in their refusal to admit women, making it virtually impossible for them to get jobs in the profession.(4)

Impressed by the talent and skills she had witnessed in the female workforce during the war, Rachel Parsons was radicalised by this development. At a meeting of the National Union of Women Workers at Harrogate in October 1918, she spoke in support of female munitions workers who ‘wish to study and learn from a scientific point of view’. As a leading member of the National Council of Women, she campaigned for equal access, regardless of gender, to all technical schools and colleges.

In January 1919, Rachel and her mother, Katharine, established the Women’s Engineering Society, with Rachel as the first president and Caroline Haslett, an electrical engineer, as secretary. The following year, Rachel helped to create Atalanta Ltd, an all-female engineering firm. She served for three years on the London County Council and stood (unsuccessfully) for Parliament in the 1923 election, when there were only two women MPs. Over two decades she devoted much of her energy to campaigning for women’s employment rights. Her political philosophy was encapsulated in a magazine article of 1919:(5)

‘Women must organize – this is the only royal road to victory in the industrial world. Women have won their political independence; now is the time for them to achieve their economic freedom too. It is useless to wait patiently for the closed doors of the skilled trade unions to swing open. It is better far to form a strong alliance, which, armed as it will be with the parliamentary vote, may be as powerful an influence in safeguarding the interests of women-engineers as the men’s unions have been in improving the lot of their members. And since the women who have taken up this profession were drawn from every rank of society, let them continue this co-operation. Let them strive for an ideal higher than trade unions have up to now set before them, and form an alliance that shall recognize no distinctions of class, take part in no class war, but which shall go forward with the aim of securing fair play for women in the industrial world.’

Rachel Parsons was one of the great unsung heroes of early 20th-century feminism. Her mother, a leader of the suffragettes in northeast England and a pioneer of the Girl Guide movement, had encouraged her daughter every step of the way. The two women had penetrated a totally male-dominated world and opened people’s eyes to new possibilities in the workplace. Having seen what great heights female workers had attained during the war, Rachel used this knowledge to blaze a trail for the army of ambitious women who followed in her wake, not just in engineering but in the many different trades and professions from which women had traditionally been excluded.

1. It was not until 1948 that women were allowed to become full members of Cambridge University and receive degrees.

2. Katharine Parsons, ‘Women’s Work in Engineering and Shipbuilding during the War’, NECIES Proceedings, vol. XXXV, 1918–19.

3. L. K. Yates, The Woman’s Part, A Record of Munitions Work, Hodder & Stoughton, London, 1918.

4. When the Amalgamated Engineering Union finally voted to admit women at the start of the Second World War, 100,000 female engineers joined almost immediately.

5. Rachel Parsons, from an article in the National Review, vol. LXXIV, 1919–20.

For more information, see www.parsonstown.info

Henrietta Heald is the author of Magician of the North, a life of the Victorian inventor and industrialist William Armstrong, which was shortlisted for the Best First Biography Prize and the Portico Prize. Queen of the Machine, the extraordinary story of Rachel Parsons and the Parsons family, is due for publication in 2015.