By Gauri Ratti

“Without the love of research, mere knowledge and intelligence cannot make a scientist.”

– Irène Joliot-Curie

Belonging to a truly exceptional category of interdisciplinary scientists, Irène Joliot-Curie (1897-1956) holds the reputation of the only daughter of two Nobel Prize in Science winners to win a Nobel Prize herself. The Curie family’s revolutionary contributions to the fields of radioactivity, radiology, and battlefield medicine simply cannot be understated. It begs the question of how such intellectual excellence carried forward through generations. Crucial to Irène Joliot-Curie’s development was the interdisciplinary, rigorous educational institutions that she had access to from a young age, and her genuine love of scientific inquiry, diverse range of curiosities, and genuine appreciation for the humanities, which, I would argue, truly distinguishes one’s success in scientific research.

Born on September 12th 1897, a mere 6 years before her parents were awarded their Nobel Prize in Physics, Joliot-Curie was welcomed into a family of academic excellence. Due to the tragic death of her father, Pierre Curie, in 1906, she was raised primarily by her mother Marie Skłodowska-Curie and her grandfather Eugène Curie, who played a substantial role in her access to interdisciplinary education during her youth. Education was always of utmost importance during Joliot-Curie’s upbringing. She was sent to academically rigorous institutions from an early age, where her talent and aptitude for Mathematics was initially discovered. Her mother made the decision to hone in on this talent, and alongside several French scholars at the frontiers of research and innovation at the time formed a privatised schooling system named ‘The Cooperative’. This was a gathering of nine pupils, being the children of distinguished academics in France who held great academic potential themselves. They received home-schooling from specialists in various subject areas, with a varied curriculum spanning the principles of science, languages (including Chinese), and fine arts. Receiving this form of specialised education and encouragement from her family to pursue intellectual development, the young Joliot-Curie readily formed a passion for learning, self-expression, and scientific inquiry. This was especially commendable during a time when women had not yet had access to the vote in France (it would take until 1944), and an education was one of the only paths to power and autonomy for women in society.

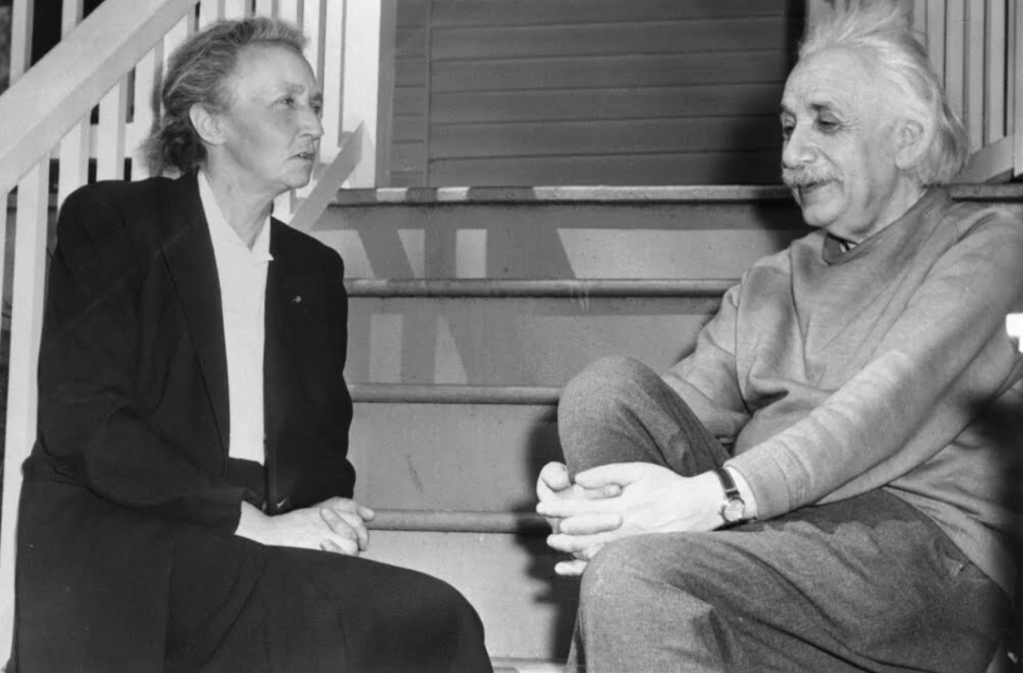

© Smithsonian Institution Archives, Accession 90-105, Science Service, Records

Beyond ‘The Cooperative’, Joliot-Curie’s education remained rigorous. She began pursuing undergraduate studies within the Faculty of Sciences at the Sorbonne, before they were interrupted by the outbreak of World War I in 1916. Despite the significant challenges this posed, Joliot-Curie continued pursuing education and training. She undertook an additional nursing course to aid her mother’s efforts on the battlefield, where she soon began assisting as a nurse radiographer. At the mere age of 18, Joliot-Curie was singlehandedly running radiology units in battlefield hospitals in Belgium, where she taught doctors and nurses how to locate shrapnel in wounded bodies using X-ray machines, as well as using them herself on the Belgian front. Her efforts in teaching alongside her contributions to diagnostics and treatment on the front lines of war earned her a military medal, and sharpened her understanding of radiology. This also exemplified the interdisciplinary expertise she held at a young age, as battlefield radiology requires an extensive knowledge of physics, biology, and human anatomy.

After the war, Joliot-Curie demonstrated a consistent effort to educate herself to the highest possible standards. She gained a second Bachelor’s in Physics and Maths at the Sorbonne in 1918. Her Doctorate followed. It was awarded in 1925, for a thesis which examined the alpha decay mechanisms of Polonium, the element discovered by her parents, and named after her mother’s country of birth, Poland. Beyond her formal education, Joliot-Curie’s research focused on the study of atomic nuclei, alongside her husband, chemical engineer Frédéric Joliot.

Irène and Frédéric’s joint research saw tumultuous outcomes at the beginning; they conducted experiments with gamma rays, which led to the identification of positrons and neutrons, although they were unable to interpret these results as we now know them. Frédéric was the first scientist to accurately calculate the individual mass of the neutron, and his joint experiments with Irène using alpha radiation to target aluminium led to the discovery that protons can transform into neutrons and positrons, which is now commonly referred to as β+ decay. Their breakthrough discovery involved the irradiation of natural isotopes such as boron, aluminium, and silicon with alpha particles, leading to the creation of radioactive isotopes such as radioactive nitrogen, radioactive phosphorus, and silicon–conversions that occur through the β+ decay mechanism. This discovery was especially profound as it took place during an era where the applications of radioactivity in medicine were accelerating rapidly, and the only way for scientists to extract radioactive elements was from natural ores, which was an extremely costly and challenging process. Joliot-Curie’s discovery of manufactured radioactive atoms therefore allowed scientists to produce these radioactive isotopes more efficiently and affordably for various uses in diagnostic and therapeutic medicine. Receiving the Nobel Prize for Chemistry in 1935 for this discovery of artificially created radioactive atoms, Joliot-Curie joined the line of esteemed and awarded scientists in her family.

Joliot-Curie’s contributions to scientific advancement, particularly in the field of cancer research, are invaluable. Her later research focused on the creation of the first nuclear reactor in 1948, defining the beginning of nuclear energy as a sustainable source of power in France. However, radiation exposure is as dangerous for the health as it can be useful in a controlled environment. Joliot-Curie was eventually diagnosed with leukaemia, potentially due to the accidental exposure to radiation she received when a sealed capsule of Polonium exploded on her laboratory bench in 1946.

Much of Joliot-Curie’s later work was focused on political activism. As a couple, the

Joliot-Curies were strongly anti-fascist, and opposed Nazism around the outbreak of World War II. Her husband’s association with the Communist Party led Irène to be detained on Ellis Island upon her third visit to the United States, where she was to speak in support of Spanish refugees at the request of the Joint Anti-Fascist Refugee Committee’s invitation. She was an avid supporter of the feminist movement, highlighting the unjust barriers in place for women in academia through speaking at feminist rallies, International Women’s Day conferences, and repeatedly applying to the French Academy of Sciences in order to draw attention to the fact that, outrageously, they did not accept women into the organisation. Moreover, the Joliot-Curies were firm advocates for peace, demonstrated by how they placed their documentation of nuclear fission research in vaults at the French Academy of Sciences on the 30th October 1939, due to fears about their research being used for military purposes. Their work remained hidden there for the following decade.

© Bettmann / Getty Images

Joliot-Curie held various major committee positions over the course of her career, including the National Committee of the Union of French Women and the World Peace Council. As a result, she not only had a commendable impact on progressing the application of physics principles in medicine, but also on advocating for women’s education and anti-war movements during an incredibly politically tumultuous era. This emphasis on interdisciplinary education and rigorous scientific inquiry, combined with her experiences with battlefield medicine, defined her ability to achieve meaningful scientific breakthroughs, and demonstrated her true resilience in the face of massive upheavals throughout her career and life. During an era of increasing anti-intellectual sentiment and massive funding cuts for scientific research, especially whilst collaboration across scientific disciplines is crucial for progress, Joliot-Curie’s adaptability and perseverance serves as an inspiration for aspiring scientists. Her academic success, humanitarian efforts, and advocacy for women’s rights to an education, is a true testament to the importance and impact of curiosity across boundaries.

References

IRÈNE JOLIOT-CURIE. NobelPrize.org. Nobel Prize Outreach 2026.

https://www.nobelprize.org/stories/women-who-changed-science/irene-joliot-curie/

Britannica Editors. “Frédéric and Irène Joliot-Curie”. Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/biography/Frederic-and-Irene-Joliot-Curie

“This Month in Physics History: March 1880: The Curie Brothers Discover Piezoelectricity.” APS News, American Physical Society, March 2014, https://www.aps.org/archives/publications/apsnews/201403/physicshistory.cfm

Teare, Harriet. “Irene Joliot-Curie: Pioneer of Atomic Science.” Bluestocking Oxford, 1 June 2008, https://blue-stocking.org.uk/2008/06/01/irene-joliot-curie-pioneer-of-atomic-science/.