By Lola Lucas

In many ways, the life and literary career of Nella Larsen is one marked by duality. Born to a white Danish immigrant mother in Chicago in 1891, Larsen became a defining voice of the Harlem Renaissance, a significant African American cultural, intellectual and artistic movement in 1920s and 30s New York, associated with figures such as Langston Hughes and Louis Armstrong. Larsen released two novels in quick succession, (Quicksand in 1928 and Passing in 1929), before falling into obscurity following a plagiarism charge against her short story ‘Sanctuary’ in 1930, which was later overturned. Her psychologically complex female protagonists and sophisticated exploration of the interwoven issues of class, race and gender make her, in my eyes, one of the most compelling American writers of the 20th century; and yet, she remains frustratingly misunderstood, with even the most sophisticated and influential readings of her work ironing out these complexities and assigning her to one side or another of reductive binary debates.

Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2001921

Quicksand appeared at a time of controversy within the literary and political circles of Harlem, when prominent intellectual figures such as W. E. B. Du Bois felt that African American literature should present a respectable and positive image of the Black community, thereby serving to “uplift” the race. It is in this context that Du Bois reviewed Quicksand alongside Claude KcKay’s recently published Home to Harlem, placing the former on the positive “representative” side of the debate, and the latter on the unhelpful “realist” side. But Quicksand in fact satirises the middle class members of the Harlem intellectual circle who celebrated Larsen’s work in the late 1920s, nowhere more keenly than in the narrator’s description of her host Anne Grey:

She hated white people with a deep and burning hatred […] But she aped their clothes, their manners, and their gracious ways of living. While proclaiming loudly the undiluted good of all things Negro, she yet disliked the songs, the dances, and the softly blurred speech of the race. Toward these things she showed only a disdainful contempt, tinged sometimes with a faint amusement. Like the despised people of the white race, she preferred Pavlova to Florence Mills, John McCormack to Taylor Gordon, Walter Hampden to Paul Robeson. Theoretically, however, she stood for the advancement of all things Negroid, and was in revolt against social inequality.

This respectable image Larsen perhaps sought to complicate when she dedicated her second novel Passing to Carl Van Vechten, the white author of the controversial Nigger Heaven (1926), and his wife Fania Marinoff, both close friends of Larsen. Van Vechten received the precise opposite of a rave review from Du Bois, who described his novel as “a blow to the face” and a “caricature” of Black life in Harlem, writing that “Life to [Van Vechten] is just one damned orgy after another, with hate, hurt, gin and sadism”. For Du Bois, at least, Nigger Heaven is a far cry from the respectable world of Quicksand, but Larsen’s insistent literary association with Van Vechten shows a reluctance to be ascribed to any one literary or social milieu.

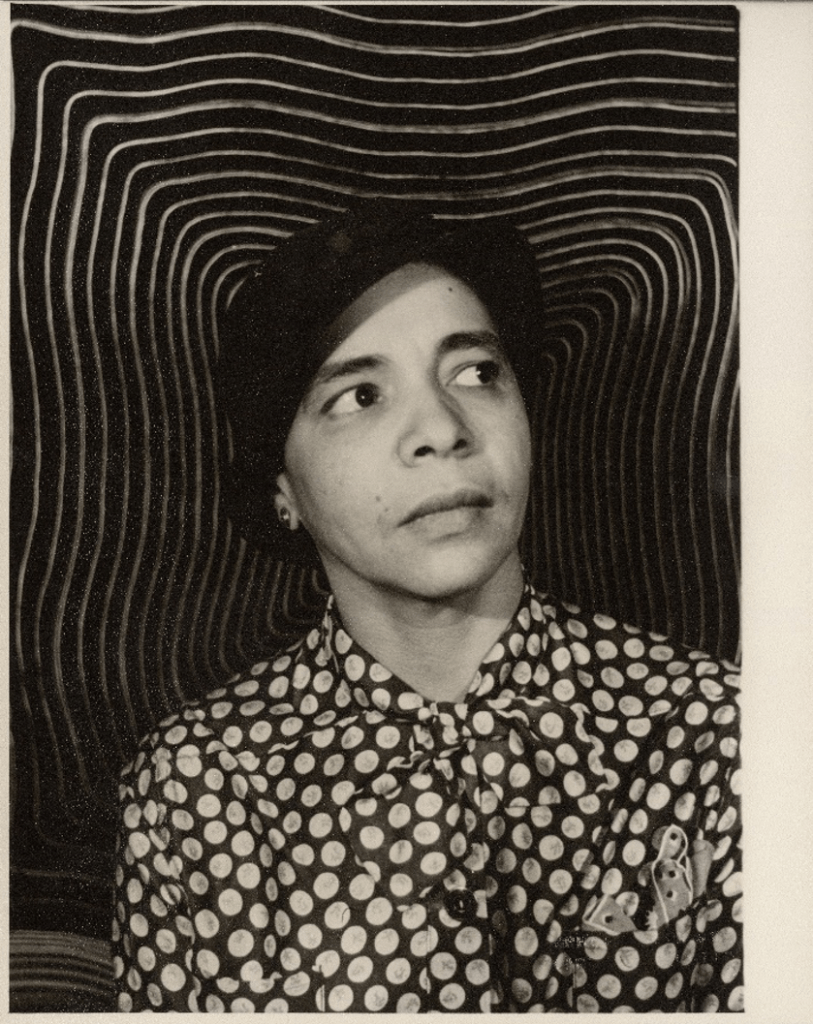

Photographs of Prominent African Americans. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/16198529

What comes through in both of Larsen’s novels is a sense of splitting or duality, an inability or even unwillingness to fit herself into any binary category. “Why couldn’t she have two lives, or why couldn’t she be satisfied in one place?” Helga Crane asks herself, the biracial protagonist of Quicksand who moves from the American South to Chicago to New York to Denmark and back again, flitting bird-like from place to place in search of a sustainable individual identity, a search that proves impossible among both Black society in “painful America” and white society in Copenhagen. In Passing this sense of splitting is only intensified, the protagonists Irene Redfield and Clare Kendry representing a kind of split-consciousness, two sides of the same coin, one embracing African American society in Harlem and the other passing as a white woman and married to a vehement racist. Irene (from whose perspective the story is told) is constantly agonising over the “ties of race” that bind her to Clare, even as Clare publicly denies them in performing whiteness. In both novels Larsen exposes not only the instability of racial categories and the effect of racial inequality on her protagonists, but also the compounded difficulty of facing these inequalities and uncertainties as a woman, emphasised by the role that motherhood plays in their lives and their identities. Clare remarks that “being a mother is the cruellest thing in the world”, as her daughter is what ties her to her husband and the white world that she now feels stifled by. For Helga, too, life comes to be defined by childbirth and motherhood, trapping her in the “unbearable reality” with which the novel ends.

Following Larsen’s return to nursing, little was written about her novels until several decades after their initial publication, when the work of female writers was being “rediscovered” as part of the feminist movement in the 1980s. This new wave of interest in Larsen’s work was, however, in some ways plagued by the same impulse as before, seeking to ascribe to Larsen one of two chief “purposes”. In the introduction to her significant 1986 edition of Larsen’s writing, for instance, Deborah McDowell seems to argue that Passing is “passing” for a novel about passing – which is to say, McDowell views the “safe and familiar plot of racial passing” and the focus on the problems of the “tragic mulatto” to be serving as a “cover” for the “more urgent problem of female sexual identity”. While McDowell’s exploration of gender and sexual identity in Larsen’s work is rich and an important contribution to the field, her analysis devalues and discards the commentary that Larsen provides on race, and in this way falls into the same trap as Du Bois and those contemporary critics who sought to reduce Larsen’s writing to one side of a debate, rather than considering the ways in which both sides speak to each other through her work. See, for instance, Irene’s thoughts in the third and final section of Passing:

For the first time she suffered and rebelled because she was unable to disregard the burden of race. It was, she cried silently, enough to suffer as a woman, an individual, on one’s own account, without having to suffer for the race as well.

Irene understands these “two allegiances” as “different, yet the same”. Theoretically, the categories of race and gender are separable, she is able to conceptualise them as individual categories in her mind; but, as Irene is fully aware, in practice any separation of the two becomes impossible, as neither concept exists in a vacuum. She cannot experience life only “as a woman”, cannot relieve herself of “the burden of race”.

Carl Van Vechten Papers Relating to African American Arts and Letters. James Weldon Johnson Collection in the Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library.

https://collections.library.yale.edu/catalog/2001920

To view either race or gender as the singular force that “drives” Larsen’s novels (or to reduce her fiction to the status of “representation” and nothing else) therefore only limits our understanding of her writing and the social workings of the worlds she describes. An intersectional approach is essential to understanding Larsen’s work, and more recent criticism of the last thirty years is finally starting to make this move beyond the need to compartmentalise elements of her writing. This critical appreciation of Larsen is long overdue, and will hopefully continue to provide fascinating insights into the difficulties and complexities that the two novels both address and create when it comes to understanding race and gender in her work.

References

Butler, Judith. “Passing, Queering: Nella Larsen’s Psychoanalytic Challenge”. In Bodies that Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”. Routledge, 2011.

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Books”. The Crisis 33, no. 2 (1926): 81-82. Internet Archive.

Du Bois, W. E. B. “Two Novels”. The Crisis 35, no. 6 (1928): 202. Internet Archive.

Hutchinson, George. In Search of Nella Larsen: A Biography of the Color Line. Harvard University Press, 2006.

Larsen, Nella. Quicksand and Passing. Rutgers University Press, 1986. (Introduction by Deborah McDowell).