By Hannah Strampe

While the early Middle Ages are not usually regarded as a key period in the history of drama, one Benedictine canoness stood out amongst her contemporaries and contributed greatly to the dramatic genre. Born in the 10th century, she lived and worked in the abbey of Bad Gandersheim, which is located in what is now central Germany. Little else is known about the life of Hrotsvitha—or Roswitha as she is also often called—but her writings survive and bear witness to an extraordinary playwright who revived the dramatic genre, created female characters with a substantial amount of agency, and conceptualised herself as an author of a significant body of work.

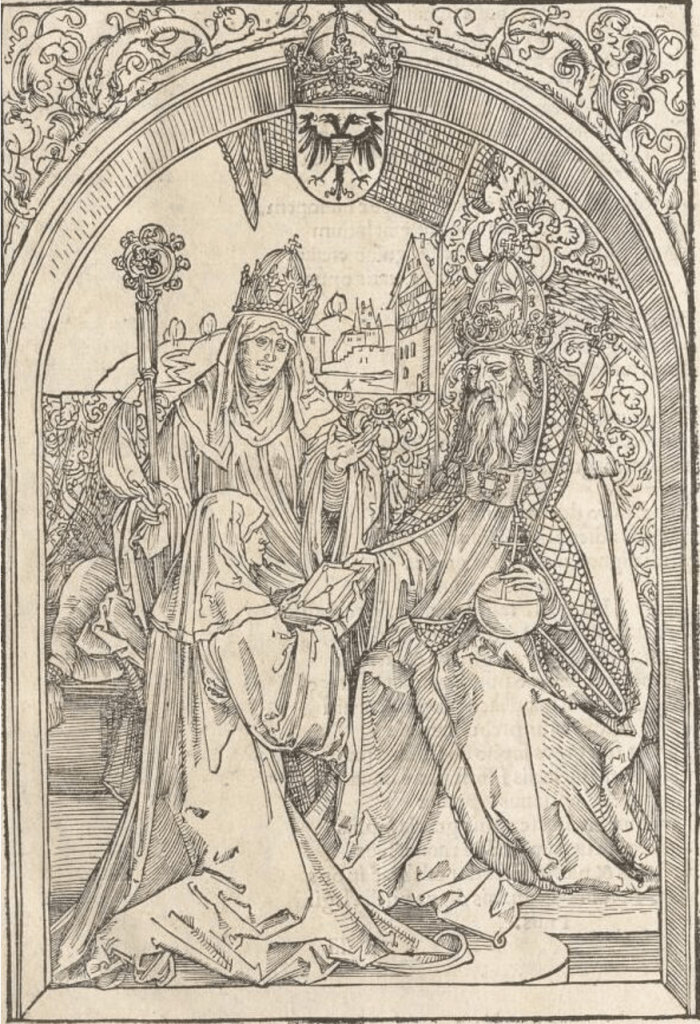

From Opera Hrosvite (1501) folio 4Av

What is certain is that Hrotsvitha was of noble birth, as Gandersheim Abbey was closely linked to the Ottonian dynasty at the time. She probably joined the abbey at a young age and received an excellent education there, with access to an extensive library. Her status as canoness offered her further freedom, as she never took permanent vows and was free to leave of her own accord.

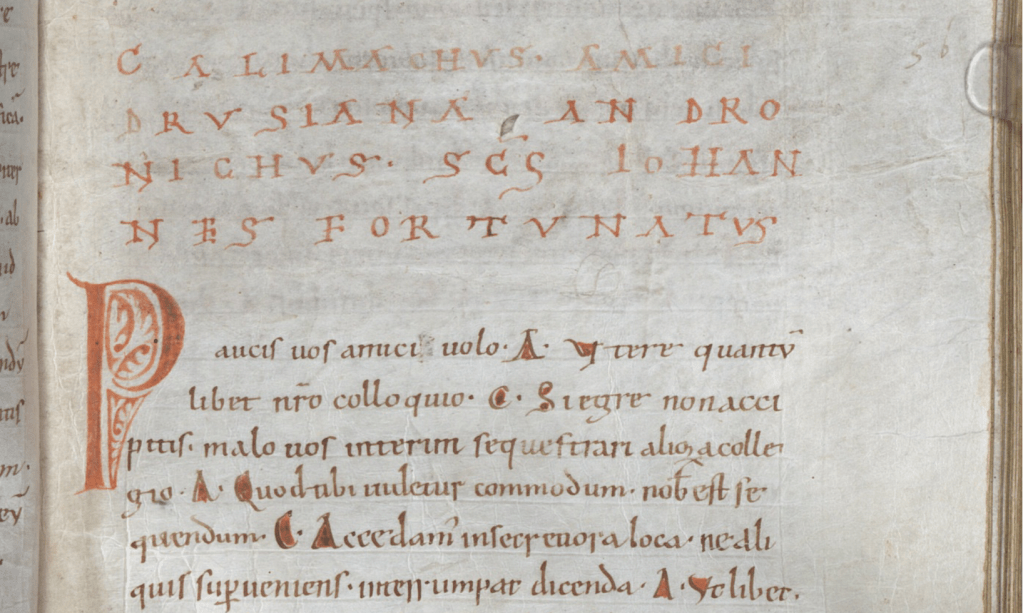

While Hrotsvitha also penned historical poems and hagiographies (biographies of saints), the most noteworthy aspect of her work is a collection of six religious plays that she wrote in the second half of the tenth century, at a time where the dramatic genre had become largely obsolete in central Europe. These plays show familiarity with the dramatic genre and while some of them can be interpreted as extended educational dialogues, others show clear, defining characteristics of dramatic writing. In the most detailed surviving manuscript of her works, the 11th century BSB Clm 14485, each play is prefaced by a list of the dramatis personae, usually five to ten characters, which are clearly marked by their initials in the following dialogue.

Additionally, and most unusually for her time, she occasionally makes use of didascalia (stage directions). It is still debated whether her plays were ever staged during her lifetime, but explicit notes in her plays that describe the movements of certain characters prove that Hrotsvitha was at least thinking of spatial dynamics and character interactions while writing.

The subjects of her plays were usually religious and moral journeys, often of young women or the men that tempted and coerced them. For this, she drew on historical legends as a source material and most of her plays centre on narratives of conversion or repentance, in which piety and virtue prevail over temptation and sin. Although these themes may now appear outdated and overly devout to the modern reader, she created strong and independent female characters within the framework of tenth century society. For example, in the play Dulcitius the pious virgins stand against the advances of the eponymous ruler Dulcitius and are able to maintain moral control. In a time when female agency was limited, her characters are articulate and steadfast and make deliberate choices about their fate. This empowerment of female characters is not superimposed by modern readings of her plays; Hrotsvitha herself wrote that she aimed to represent the triumph that occurs “when womanly frailty emerges victorious and virile force, confounded, is laid low” (Trans. Dronke 69). She thus demonstrates an awareness of gendered dynamics that she wishes to invert.

This cited passage is only one of many examples in which Hrotsvitha’s authorial voice speaks to her readers more than a millennium after her death. Multiple prefaces and letters survive in the manuscripts alongside her plays and hagiographies, in which the author of these anachronistic works emerges and offers insight into her worldview. In these paratexts she reflects on her education, the circumstances of her writing, and her sources. She confirms that she read widely, not only the Church Fathers and her contemporaries, but also classical Roman authors across different genres. Amongst the Roman playwrights she cites Terence as a definite source and stylistic guide, although it is probable that she had access to a number of classical plays. In reference to her explicit mention of Terence, she states that she wanted to elevate his style of writing by combining it with Christian morals and values, thus essentially laying the foundation for what would eventually become medieval morality plays.

In the same preface Hrotsvitha also states that she is aware of her unique position in society even amongst contemporaries and that in her circumstances it was by no means ordinary to work as a female playwright. In one instance she calls herself “clamor validus Gandeshemensis” (Preface, Liber Secundus) which translates to the “strong” or “mighty voice of Gandersheim”, demonstrating that she was conscious of her talent and influence. After the preface to the plays follows a letter of hers to benefactors of her work, in which she tries to unite her position with the social norms of her age and comments that it is unusual that a woman should receive such financial and social support in her endeavours. Ultimately, she attributes her unusual circumstances to a combination of talent and her excellent education, and while she sees the roots of her talent as divine, she focuses heavily on the importance of developing her skills through learning and work.

By witnessing Hrotsvitha’s authorial voice through her prefaces and letters in combination with her unique plays, a picture of an accomplished and well-regarded writer arises. While privileged circumstances allowed her an exceptional position, she seized the means available to her in order to grant voice to strong female characters that embody the same moral strength and intelligence as her. Her choice to write a considerable part of her oeuvre in an obsolete genre and subsequently enjoying great success with this, while making lasting contributions to its literary tradition speaks for itself. Almost as an afterthought she managed to establish herself as an authorial figure, whose intentions and views are still accessible today—a feat that few mediaeval writers would ever manage.

Further Reading

Hrotsvitha. The plays of Roswitha. transl. by Christopher St. John, Chatto & Windus, 1923.

Butler, Mary Marguerite. Hrotsvitha: the Theatricality of Her Plays. Philosophical Library, 1960.

Gold, Barbara. “Hrotsvitha Writes Herself,” Sex and Gender in Medieval and Renaissance Texts: The Latin Tradition . State University of New York Press, 1997, pp. 41- 70.

Cescutti, Eva. Hrotsvit und die Männer. Wilhelm Fink Verlag, 1998.