By Alana Cottey

Radclyffe Hall (1880-1943) was born Marguerite Radclyffe-Hall to a wealthy English household, but would later be known as John to friends and lovers. Her novel Adam’s Breed (1926) received the Prix Femina and James Tait Black Prize, yet real fame came with the banning of The Well of Loneliness upon its publication in 1928. Deemed ‘obscene’ for depicting romantic relationships between women, it remained banned from British publication until 1949. Nevertheless, sometimes known as the ‘first lesbian novel’, it was intensely discussed within lesbian communities in the mid to late 20th century. While some found it revelatory and self-affirming, others criticised its use of stereotypes and its portrayal of lesbians as tragic outcasts. These debates centred on the characterisation of its protagonist, Stephen Gordon.

The Well traces Stephen’s development from birth to young adulthood in a Bildungsroman style. Her conventionally masculine name reflects the idea that she is ‘born different’. Her “narrow-hipped, wide-shouldered” physique is noted, and her parents and neighbours soon notice her preference for fencing and hunting over ‘feminine’ pursuits. In childhood, she lacks self-determination, but is resolute against conformity, protesting against the dresses and long hair prescribed by her mother in “impotent defiance”. Through such interactions, Hall develops a character with complex and layered emotions. These include confused sorrow at her own sense of difference – in a subtly heart-wrenching moment, she asks her father, “is there anything strange about me?” This disempowering self-doubt felt by such a vibrantly active and spirited adolescent speaks strongly for the value of recognition and acceptance.

Some readers have found Hall’s use of masculine stereotypes difficult, especially in passages that emphasise Stephen’s ‘unfeminine’ appearance and paternalistic desire to “protect” women she loves. In this, Hall was influenced by late nineteenth and early twentieth century sexology, a now outdated school of social science that sought to explain homosexuality and bisexuality through biological and psychological models. Prominent members of the school included Richard von Krafft-Ebing, whose Psychopathia Sexualis (1886) is read by Stephen and her father in The Well, and Havelock Ellis, a British sexologist whose theories particularly influenced Hall. His model of ‘inversion’ framed homosexuality as a biological anomaly that gave women ‘male’ characteristics, and vice versa. Hall self-identified as an ‘invert’, and applied the term to Stephen – the idea that one does not become a lesbian, but is born that way, was central to Hall’s plea for acceptance. Through Stephen, she sought to demonstrate that lesbianism was not a choice to be admonished or ‘cured’, but was natural and God-given.

These ideas mapped uneasily onto a late twentieth century paradigm of lesbian feminism and feminist literary criticism, which emphasised the constructed nature of gendered inequalities and sought to recentre women’s subjectivities. Queer literary criticism further rejected rigid categorisations of gender and sexual identities. Hall’s belief that these could be explained ‘scientifically’, and her attribution of normative ‘masculine’ qualities to Stephen in order to prove this, therefore generated increasingly negative responses. For example, Faderman and Williams critiqued that Stephen perpetuated a biologically determinist image of lesbianism that rejected femininity. Instead, they preferred Hall’s The Unlit Lamp (1924) or Virginia Woolf’s Orlando (1928) as truly ‘lesbian feminist novels’, perhaps because these highlighted the importance of choice and flexibility in their protagonists’ lives and relationships. These works were quite veiled representations of lesbianism – while Hall aimed to be more explicit in The Well, her creation of a single lesbian image left the novel subject to critique. However, it should also be recognised that many readers found Stephen not merely a sexological case study, but an inspirational survivor in a time of censure.

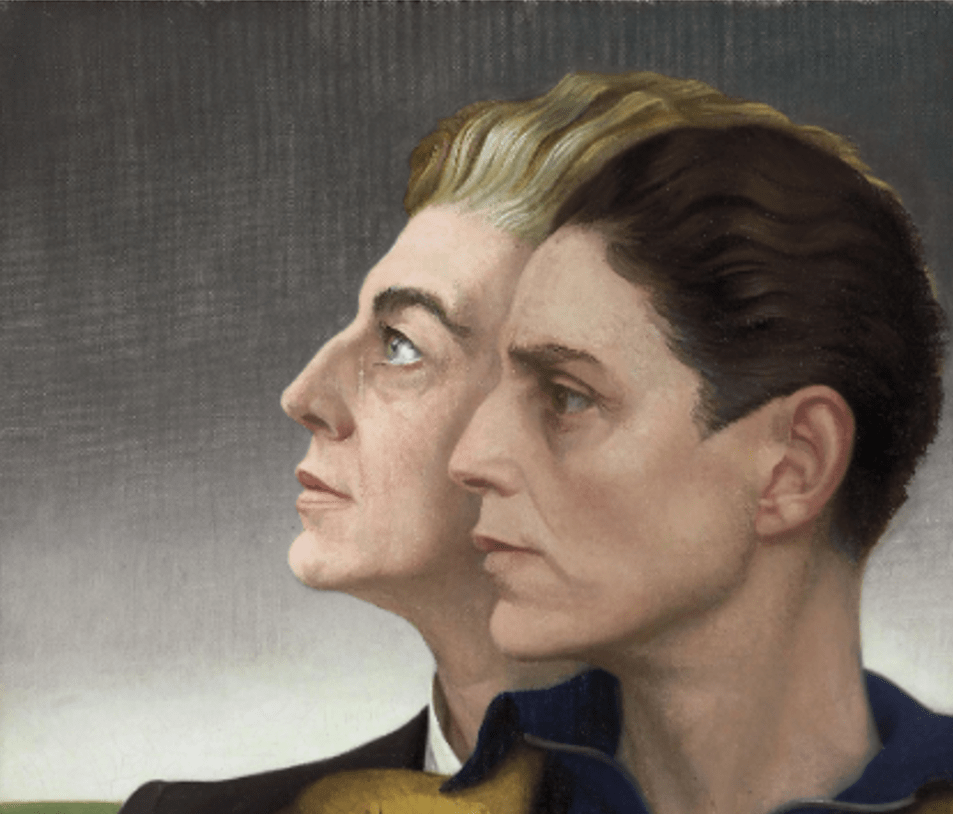

Medallion by Gluck (Hannah Gluckstein) | Obelisk Art History

Stephen’s identification with her father and alienation from her mother is partly an element of sexological influence, but also highlights the restrictiveness of contemporary gender norms. Her mother Anna is “the archetype of the very perfect woman”, “all chastity” and possessing “calm beauty”, and is dichotomised with Stephen’s refusal to meet these standards. Anna becomes an allegorical representation of a hegemonic feminine heterosexuality that does not accommodate alternative identities. The distance between them is heightened by her ignorance of Stephen’s ‘inversion’ long after it is revealed to the reader and her father, when the latter reads Krafft-Ebing’s work. When Anna learns of Stephen’s love for another woman, her cruel reaction makes her symbolic rejection of her daughter concrete. On the other hand, when Stephen joins her father hunting, neighbours mark her riding astride as not “modest”. By emphasising Stephen’s “self-consciousness” and dejection at these multiple exclusions, Hall shows the harmful binarism of masculinity and femininity that shaped expectations of bodies and behaviours. She further does this through Stephen’s loathing of neighbouring children Roger and Violet Antrim. These characters are hyper-gendered, and negatively so – Roger is “full to the neck of male arrogance”, while Violet is a “sop” and “full of feminine poses”. Here, Hall communicates the strikingly modern message that conformity to gendered expectations does not equal virtue.

Stephen’s youth is not all spent in alienation and misery. Her home, Morton, is a sanctuary where she is accepted, spending her days with the horses and groom, Williams, or studying under her governess, Puddle (who is hinted as an ‘invert’ herself). These relationships help Stephen to flourish emotionally, physically, and intellectually, creating a counterbalance that refuses to uphold intolerance as the norm.

Stephen’s romantic relationships are also key to her development and to Hall’s depiction of lesbian relationships more broadly. Her first real romance is with Angela Crossby, a married woman who takes advantage of Stephen’s feelings as a diversion from her unpleasant husband. Stephen shows great loyalty to the undeserving Angela, and naively buys her expensive presents in the hope that she may leave her husband. This contrasts her later relationship with Mary Llewelyn, who she meets in the wartime ambulance service. With Mary, Stephen’s anxious desire to please and protect are rewarded with devoted love. Her contentment when they begin living together creates a sense of resolution, as Stephen’s hardships seem finally to end. She now feels “sick of tacit lies” surrounding her sexuality, an impulse that underpinned the emphasis on ‘coming out’ that developed in the 1970s. In this way, Stephen’s story speaks transhistorically to visions of liberation and happiness – finding love is endowed with an empowering quality that heals the wounds of the misunderstood child.

However, the triumphant coming-of-age narrative collapses into a tragic conclusion when Stephen gives Mary up, urging her to marry Martin Hallam, a childhood friend of Stephen’s. Many readers have described resentment at this denial of happiness to a character whose social and emotional journey resonated with their own. Hall’s own long-term partnerships suggest that she did not truly believe all lesbian relationships to be ‘doomed’, but was driven to depict them as such to evade censorship. Indeed, through the character Valerie Seymour, she articulated a more optimistic view. Valerie assures Stephen that she and Mary could make a good life together, expressing frustration at her decision to sacrifice the relationship. But, as Valerie laments, Stephen was “made for a martyr” – one that offers an invitation to build new futures over a well of hardship.

In The Well, therefore, Hall created a character bounded by censorious attitudes, but who in many ways defies them. Stephen is emotionally complex – naïve and frustrating at times, but sincere and loyal. In short, she is incredibly human: readers have continued to resonate with her hopes and hardships, and her anxiety to belong but refusal to conform. However, for many, Hall’s use of sexological concepts recalls an era when lesbianism was pathologized and treated, at best, as something to be tolerated rather than celebrated. The Well’s plea for acceptance, then, tends to leave a bad taste in the mouth in a new age of privileged visibility and pride. Hints of these can be seen in Stephen’s journey, but can be obscured by Hall’s determined crafting of a particular lesbian image. Nevertheless, The Well was a pioneering work that facilitated ongoing debates about lesbian identity, expression, and cultural representation. Hall’s creation of Stephen opened new possibilities for literary exploration of queer identities – as biographer Glendinning quotes of Vita Sackville-West, “if one may write about [homosexuality], the field of fiction is immediately doubled”.

Note: This article uses she/her pronouns in order to centre Hall’s contribution to literary representations of queer and gender non-conforming women*, but acknowledges that many different readings of her life are possible.

References

Baker, Michael, Our Three Selves: The Life of Radclyffe Hall. London: Hamish Hamilton, 1985.

Faderman, Lillian, and Ann Williams, ‘Radclyffe Hall and the Lesbian Image’, Conditions 1:1(1977), pp.31-41.

Glendinning, Victoria, Vita: The Life of Vita Sackville-West. London: Weidenfeld and Nicholson, 1983.

Hall, Radclyffe, The Well of Loneliness. London: Virago Edition, 1982.

Newton, Esther, ‘The Mythic Mannish Lesbian: Radclyffe Hall and the New Woman’, Signs 9:4 (1984), pp.557-575.

O’Rourke, Rebecca, Reflecting on The Well of Loneliness. London: Routledge, 1989.