By Iona Mandal

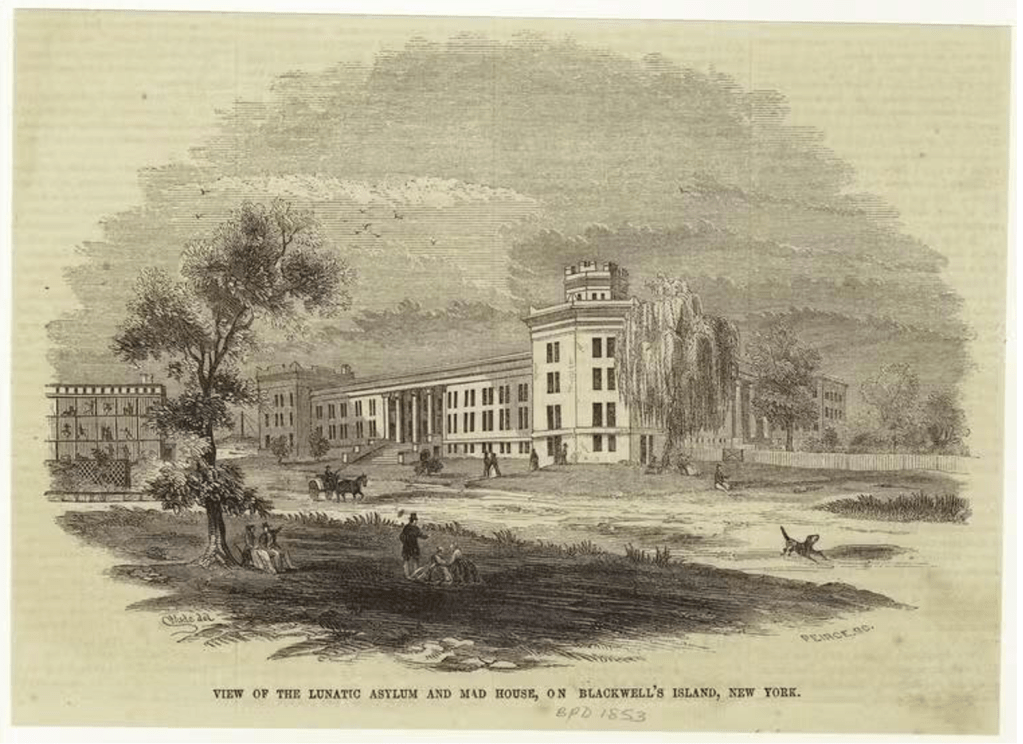

When Nellie Bly (1864-1922) walked through the doors of the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell’s Island in 1887, she was entering the machinery of a system that had long relied on secrecy to maintain its authority. Ten Days in a Madhouse (1887) is remembered today as a pioneering work of investigative journalism, functioning as a study of how institutions produce vulnerability in women, and how a woman writer, operating with little more than observation and nerve, forced those institutions into visibility. Bly’s project was not merely to report on injustice but to reveal the mechanisms through which injustice sustains itself.

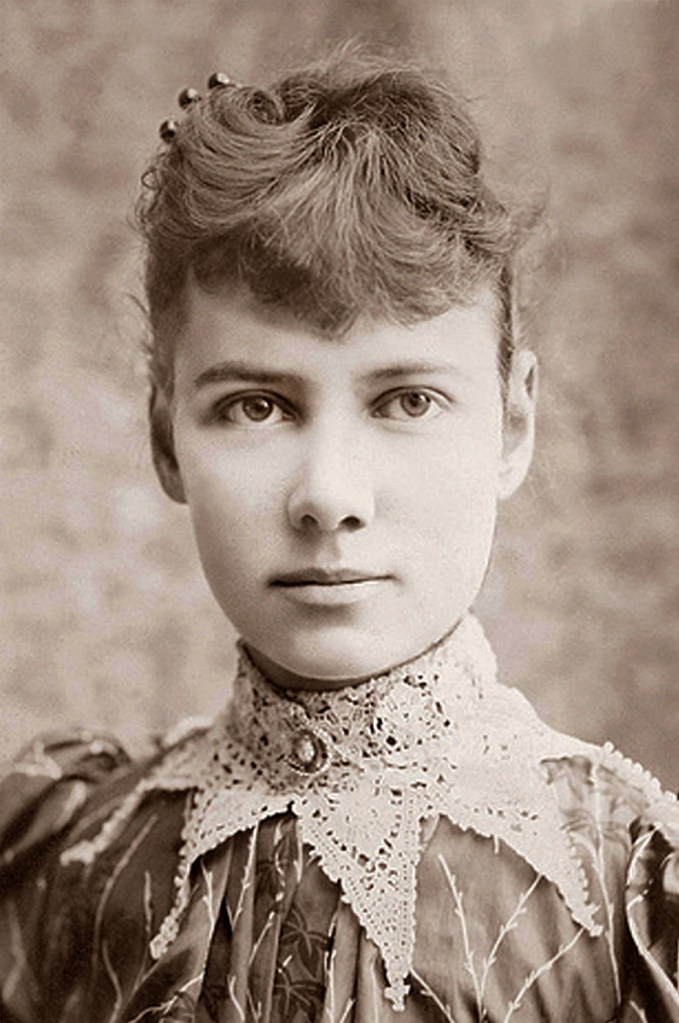

Crucial to understanding the force of Bly’s intervention is her position within what critics have termed “stunt-girl journalism”. As Karen Roggenkamp, a critic of journalistic literature, argues, late nineteenth-century newspapers (particularly those under Joseph Pulitzer) thrived on dramatic, highly embodied reportage that blurred the lines between fact and fiction. Reporters became protagonists, and news became a narrative designed to “triumph over mere imagination,” with Bly representing the genre’s ideal figure: youthful, daring, and able to convert lived risk into narrative authority. Her asylum investigation thus functioned not only as an exposé but as the most radical iteration of a literary-journalistic experiment in which the female reporter’s body became the very site of truth production.

© United States Library of Congress’s Prints and Photographs division via Wikimedia Commons

Bly’s method was radical in its refusal of professional distance. Rather than interviewing patients from the safe remove of a reporter’s notebook, she became one of them: subject to the same caprice, the same humiliations, the same absolute loss of control. The asylum’s power depended on the discrediting of women’s subjectivity: once inside, no woman’s testimony could be trusted, no protest recognised as truthful. Bly’s first achievement was to expose this logic by inhabiting it. She showed how the asylum’s authority emerged not from medical knowledge but from the ability to declare a woman “insane” and to let that declaration erase everything she might say in her own defence.

Yet as Jean Marie Lutes reminds us in her book examining American women journalists working between 1880 and 1930, stunt reporting carried its own contradictions. Newspapers relied on women reporters precisely because their perceived vulnerability heightened the drama and moral stakes of the story. The stunt girl was expected to be brave, yet her bravery was made legible only through the dangers she faced; she was a spectacle of female risk, deployed to evoke shock, sympathy, or reformist outrage. Lutes notes that while these reporters were granted extraordinary assignments, their authority was shaped, and sometimes constrained, by editorial demands for spectacle and sentiment. Bly subverted this dynamic by refusing victimhood: she used the very framework that exploited female vulnerability to expose the structures that manufactured it.

This tension between the role stunt reporters were instructed to play, and the one Bly insisted on taking, illuminates what Ten Days in a Madhouse demonstrates so powerfully: how little was required for a woman to disappear. Bly records the thin pretexts for institutionalisation: poverty, foreignness, simple exhaustion, as though the system were a sieve designed to catch those least able to protect themselves. Women who did not speak English were deemed incoherent; women tired from overwork were deemed unstable; and those unaccompanied by family or funds were viewed as suspicious. For Bly, these patterns revealed something essential: insanity was not always a medical diagnosis but a social verdict, one that punished women for occupying the wrong place in the world at the wrong time.

Inside, Bly catalogued the operations of power that enacted these horrors. She paid attention to what institutions prefer to render invisible: the texture of daily life, the ways small indignities accumulate, and the violence disguised as routine. The ice-cold baths that women were forced to endure were disciplinary gestures which kept them compliant, and the inedible food was an assertion that the inmates were not worth nourishing. The constant surveillance as matrons hovered over every conversation made intimacy impossible and solidarity dangerous. Bly recognised that the asylum operated through a kind of systemic gaslighting: women were made to doubt their own perceptions because everything around them conspired to insist that they were irrational.

Bly’s writing refuses the sentimental conventions that nineteenth-century women journalists were expected to follow. She does not weep on the page; she does not ask the reader to pity her. Instead, she exposes the asymmetry of power with a journalist’s restraint sharpened into moral clarity. In one section, Bly notes how even the “kindness” of the staff functioned as a threat: a smile could be withdrawn, a whispered reassurance replaced with a command. She observes that the worst punishments were not necessarily physical but psychological: being ignored, or treated as though speech itself were an inconvenience. The result is a portrait of institutional violence that is unsentimental and devastating.

What makes Ten Days in a Madhouse particularly resonant for feminist analysis is Bly’s insight into how women’s bodies become administrative objects. She describes the ways patients were handled, lined up, inspected, scrubbed, and silenced. The women are constantly positioned: sat here, stood there, marched elsewhere, in a choreography centred on control. It is not madness which renders them powerless but the institution itself.

This recognition places Bly at the heart of the literary-journalistic transition Roggenkamp describes: the moment when the press turned to narrative immersion as a guarantee of truth. Bly exploited this shift by using the reporter’s body not as a site of sentimental spectacle (as many editors intended), but as a critical instrument. She transformed the stunt’s built-in sensationalism into a method of institutional witnessing, redirecting the gaze outward to expose the mechanisms of control that produced the very spectacle the press was hungry to consume.

Her intervention, then, was not simply to document conditions but to challenge the epistemological authority of the asylum. She insisted that the testimony of institutionalised women should matter. In doing so, she disrupted the assumption that those labelled “mad” held experiences unworthy of political consideration. Bly’s work revealed that the asylum produced the conditions under which women’s suffering could be dismissed. The brilliance of her undercover investigation lies in its reversal of this logic: by entering the institution, she forced the institution to speak.

© New York Public Library

Bly’s insistence on seeing women as credible narrators of their own suffering continues to unsettle contemporary feminist debates. She recognised that institutions do not simply silence women, but create conditions in which women appear organically silent. The asylum’s structure taught women that speaking would be futile. In her account of immigrant women locked away for no crime beyond linguistic difference, Bly shows how disposability is manufactured. It is not incidental that she describes the asylum as “a human rat-trap”: those who enter are not expected to escape, let alone to offer testimony.

After the publication of Ten Days in a Madhouse, New York allocated more funding to mental health care, improved patient conditions, and removed corrupt staff. But these reforms, though important, are not the central legacy. The radicalism of Bly’s work lies in its demonstration that journalism can function as praxis: a method for challenging who gets to speak, whose experiences are considered evidence, and how power maintains its own invisibility.

Bly understood that institutions are only as strong as the secrecy that shields them. By inhabiting the asylum rather than observing it, she shattered that secrecy, thereby reconfiguring the relationship between journalist and subject and revealing that the most transformative investigations emerge from the willingness to risk proximity.

Ten Days in a Madhouse asserts that women’s experiences under power are politically authoritative. Bly transformed her ten days of imposed silence into a public demand for accountability, making an institution which thrived on obscurity legible. This is the work she pioneered: the insistence that women’s testimony, even from the spaces designed to erase them, can still reorder the world.

References

Bly, Nellie, Ten days in a mad-house: A story of the intrepid reporter. Dover Publications: 2019.

Lutes, Jean Marie, Front-Page Girls: Women Journalists in American Culture and Fiction, 1880-1930. Cornell University Press: 2006.

Roggenkamp, Karen, Narrating the News: News Journalism and Literary Genre in Late Nineteenth-Century American Newspapers and Fiction. Kent State University Press: 2001.