By Andrea Obholzer

In The Common Reader (1925), Virginia Woolf wrote ‘The Peasants are the great

sanctuary of sanity […] when they disappear, there is no hope for the race.’ What

did Virginia Woolf know of common people? Apart from her stint teaching at Morley

College between 1905-1907 and her relationships with her servants, how many

common people did she come across? In 1906 a seventeen-year-old girl called Nina

Forrest (1887-1957) from a Manchester slum arrived at 46 Gordon Square in

London. Virginia and her siblings came to know Nina extremely well. She had just

eloped from Manchester with a young medical student Henry Lamb (1883-1960),

who wanted to become an artist. Henry’s brother Walter Lamb was at Cambridge

University with Thoby Stephen and introduced the runaway couple to his two sisters.

© Hugh Lane Gallery, Dublin

In their new Bloomsbury address the Stephens were keen to rebel against their Victorian upbringing and live independently in a modern way. On first meeting Nina in May 1906, Virginia wrote to her friend Violet Dickinson,

‘We have been landed with Miss Forrest […] She sits vaguely in the drawing room for hours and forgets whether she had tea or dinner last, whether children have meat or wine. My head spins with her stories; until I say sternly ‘Miss Forrest take my advice and learn Greek’. It is like a nightmare.’

Virginia was both fascinated and appalled by Nina, and Vanessa was shocked by her ‘regular terrible infant remarks’ and ‘appallingly sordid stories.’ Vanessa wrote to her friend Margery,

‘She told me a good deal of her history rather incoherently, but I came in the end to a fairly clear idea of her most extraordinary past existences. It’s too full of ins and outs to be repeated at length and it sounds like a medieval romance – but I believe it’s true.’

Nina’s stories were not true. In order to disguise her lowly social origins, she made up that she had been engaged to a Russian Count and rescued by Henry Lamb. Vanessa continued,

‘She seems to have been deserted by her family […] They are quite rich and they alternately neglect her entirely & have her to live with them for short intervals when they spoil her. She seems to have had no education and to have lived with some very second rate people going about from one house to another and being adopted by various friends and relations in turn.’

Virginia was less gullible than Vanessa when it came to Nina’s stories, but she was interested in her and her capacity for confabulation. When she came to write her novel of 1922, Jacob’s Room, an account based on the period when her brother Thoby was still alive (he died in late 1906), she drew on Nina to create the character of Florinda. Florinda is the distant and unreliable young woman with whom Jacob Flanders falls in love. Woolf describes Florinda as ‘wild, frail and beautiful’:

‘As for Florinda’s story, her name had been bestowed upon her by a painter who had wished to signify that the flower of her maidenhood was still unplucked. Be that as it may, she was without a surname, and for parents had only a photograph of a tombstone beneath which she said her father was buried. Sometimes she would dwell on the size of it and rumour had it that Florinda’s father had died from the growth of his bones which nothing could stop; just as her mother enjoyed the confidence of the Royal Master, and now and again Florinda was a Princess, but chiefly when drunk. Thus deserted, pretty into the bargain, with tragic eyes and the lips of a child, she talked more about virginity than women mostly do; and had lost it only the night before, or cherished it beyond the heart in her breast, according to the man she talked to.’

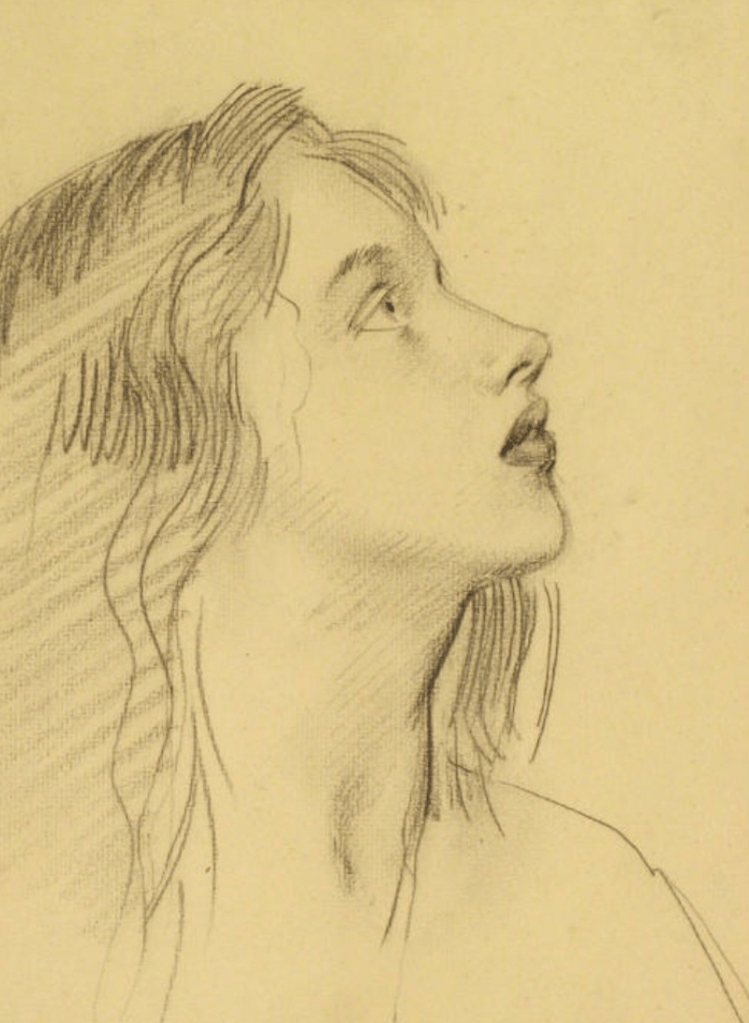

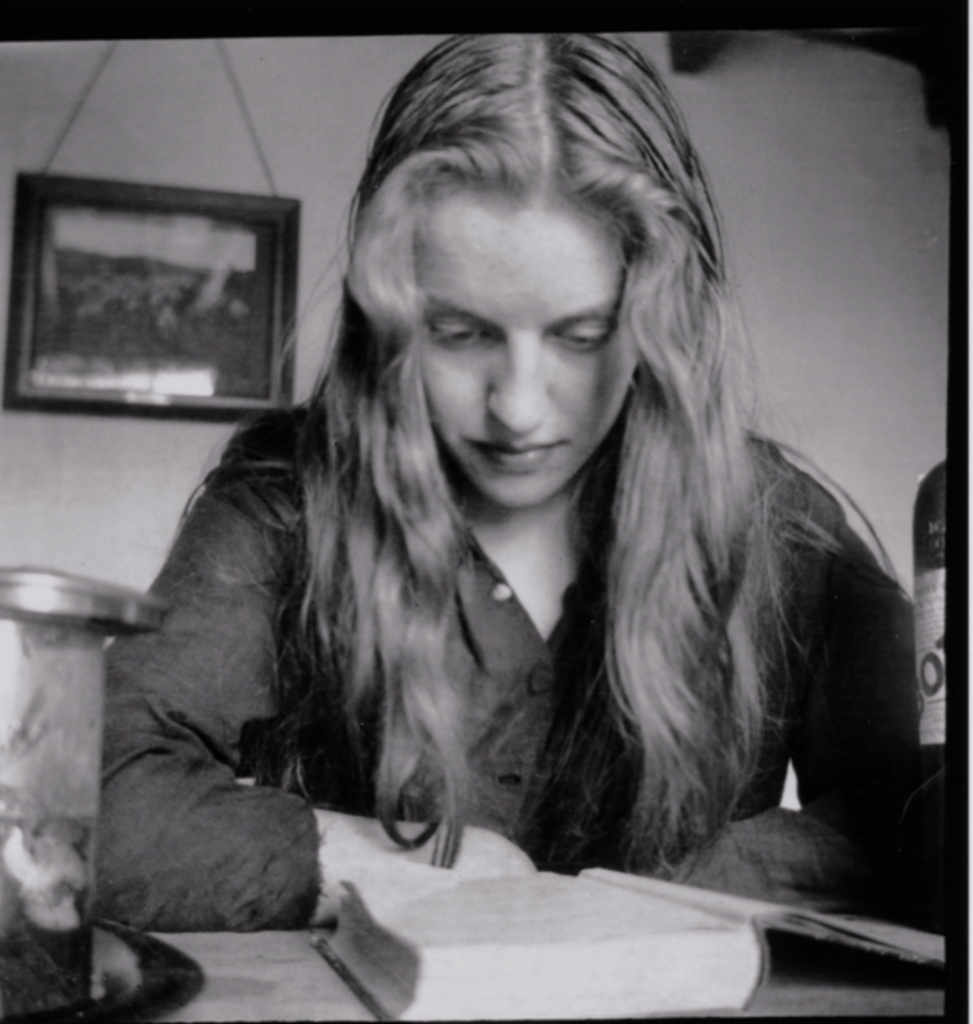

The similarities between Florinda and Nina are striking; shortly after her marriage to Lamb and on arriving in Paris and discovering there was already a famous artist’s model called Nina, Henry advised Nina to use her middle name Euphemia. Euphemia Lamb was thus born. Her inconsistent tall stories were legendary; she was exceptionally pretty with full lips and of questionable morals. During those months at 46 Gordon Square, when Vanessa painted her, it seems she entered Virginia’s imaginative life too. Virginia wrote of Nina in her diary in 1920 whilst writing Jacob’s Room,

‘I see her as someone in mid ocean, struggling, diving, while I pace the bank.’

As a working-class girl from Manchester, Euphemia had been privy to a world of promiscuity. (Greenheys, where she grew up, was known as the centre of prostitution.) She was aware of her good looks, charm, and power to sexually attract men. Euphemia was intelligent but uneducated: in 1900 girls left school at age twelve. She took the opportunity of being surrounded by bohemian intellectuals to expand her mind. We know that Clive Bell was recommending everyone at Gordon Square to read Les Liaisons Dangereuse (1782) during his courtship of Vanessa. In meeting Henry Lamb, Euphemia—by sheer luck—found a ticket to another life, one where she could learn about art and read books and discuss ideas. Not many working-class girls of the Edwardian era had this opportunity.

Euphemia became a celebrated artists’ model, painted by Lamb, Augustus John, Ambrose McEvoy and Vanessa Bell. She was sculpted by Jacob Epstein. She was a literary muse not only for Woolf but Henri Pierre Roché, who dedicated five chapters of his 1953 novel, Jules et Jim, to a character called Odile, which was based on their yearlong threesome relationship with his best friend Franz Hessel. Euphemia’s genius and vivacity are preserved in the surviving art and literature which she inspired. Her life is a testament to what a ‘common’ girl could contribute if given half a chance.

Andrea Obholzer is the author of A Bloomsbury Ingénue: The Lives and Loves of Euphemia Lamb, published by Unicorn and available now.

References

Clements, Keith. Henry Lamb: The Artist and His Friends. Bristol: Redcliffe, 1985.

Obholzer, Andrea. A Bloomsbury Ingénue: The Lives and Loves of Euphemia Lamb. Lewes: Unicorn, 2025.

Roché, Henri Pierre. Jules et Jim. London: Penguin Classics, 2011.

Woolf, Virginia. Jacob’s Room. London: The Hogarth Press, 1922.

—The Common Reader. London: The Hogarth Press, 1925.

—The Diary of Virginia Woolf (1915-19). London: The Hogarth Press, 1977.

—The Letters of Virginia Woolf: Flight of the Mind Letters Vol 1 (1888-1912). London: The Hogarth Press, 1975.

—Moments of Being. London: Pimlico, 2002.