By Jessica Phillips

I am not a punk. And if you’re at Oxford University, chances are, you aren’t either. This place is a Prime Minister machine, the epitome of ‘The Establishment’. So perhaps it is audacious for me to challenge the relationship between the Mother of Punk, Vivienne Westwood (1941-2022), and the clothes that she created. However, I do not think that the term ‘punk’ fits Westwood’s fashion brand as we know it today. The fact that the punk aesthetic has defined her legacy demonstrates the success of her fashion at shocking its audience and stoking up controversy, but ultimately it has overshadowed the more conservative politics of its designer.

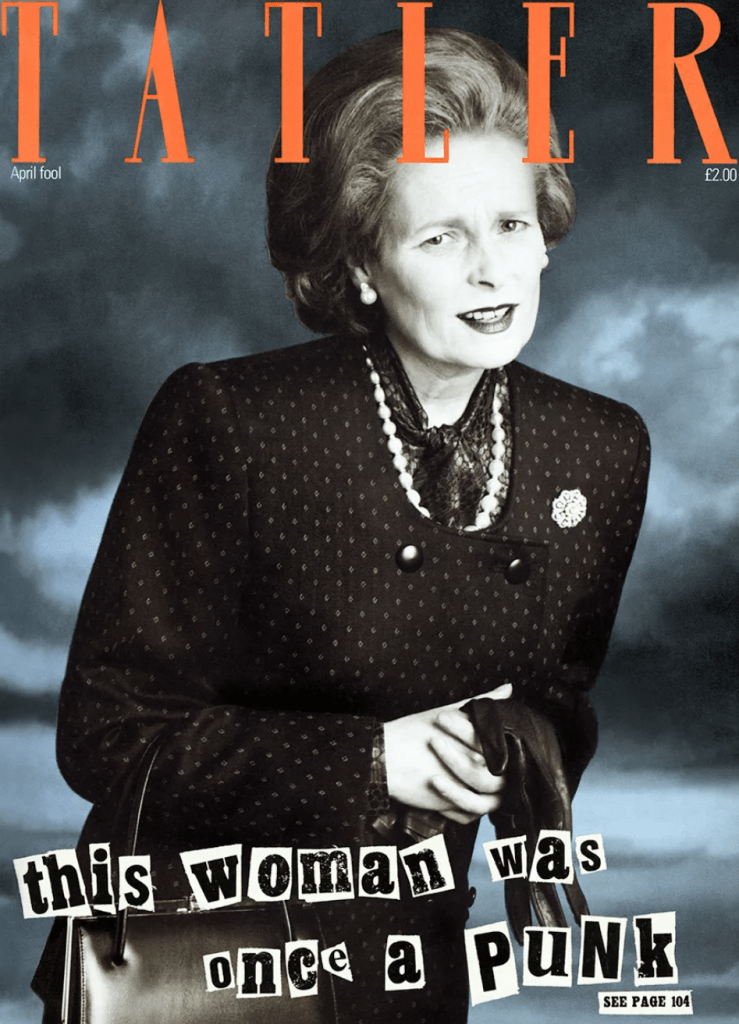

https://www.tatler.com/article/acceptable-in-the-80s

Westwood’s career in design took off in 1974 at a shop on the King’s Road, known today as World’s End. The shop underwent a series of name changes; at one point it was simply called SEX. It was under this name—loud and provocative and stretched in huge, hot pink capitals across the Chelsea shopfront—that Westwood’s relationship with punk truly began.

The designs from the shop’s early years were suitably brazen. One of the T-shirts featured a graphic print of a woman’s breasts, cheekily positioned to draw the eye to the wearer’s own chest. Another T-shirt was adorned by a graphic print of Queen Elizabeth II, her lips safety-pinned together, above the words ‘God Save The Queen’, a reference to both the national anthem and the title of a Sex Pistols song (the print was also ironically framed by the Sex Pistols lyric ‘she ain’t no human being’). These designs are unequivocally punk; they speak in the voice of common people and make a statement that attacks the establishment.

https://www.vam.ac.uk/articles/vivienne-westwood-punk-new-romantic-and-beyond?srsltid=Afm

BOorrcy8MvuEBb3TFArNUrRzBFNlUVhuabTYJgIbwxyI-chyyEosz

However, Westwood would go on to criticise the punk movement. The turning point was the Pirates collection at London Fashion Week in 1981. It drew inspiration from debonair 18th-century pirates, highwaymen and rogues. Westwood styled herself as a pirate of fashion, who plundered history and global cultures for inspiration.

Some of her punk motifs are retained in Pirates: the clothes appear mismatched; the creasing and rumpling of the fabric is emphasised; the models don slouchy boots and layer baggy clothes. These imperfectly shaped garments pushed back against the clean lines that dominated 1980s fashion—namely in lycra fitness wear, shoulder pads, and bodycon dresses.

Although the title Pirates granted the collection a feeling of rebellion, it still evoked a certain ramshackle luxury, reminiscent of the plundered riches of swashbucklers. Gold glittered on cockades and painted nails, and was smeared on the eyes and foreheads of models, who, through Westwood’s Midas touch, began to transform her punk tactics into fountains of wealth.

https://www.viviennewestwood.com/en-gb/westwood-world/the-story-so-far/#collection-filter

In the 1988 Time Machine collection, Westwood mixed historical and artistic references associated with traditional British identity. Medieval armour was remade in leather and matched with tweeds; there was a boned bustier and pair of breeches in purple velvet, boasting an opulent number of golden buttons. These designs, with firmer lines and shoulder pads creating a more refined appearance, are less ‘pirate’ and more redolent of the dandy look. Westwood was circling closer and closer to the monarchy she once openly criticised.

The allure of the monarchy is also apparent in the updated 1986 Westwood logo. Now synonymous with high fashion, it features a globus cruciger, encircled by a planetary ring, transforming a symbol of British monarchy into a shape resembling Saturn. The design is intended to portray the unity between tradition and progression, which Westwood’s fashion promotes, yet it also demonstrates the prominence of monarchy and aristocracy in Westwood’s brand.

Vivienne Westwood consolidated her relationship with the British monarchy when she received an OBE in 1992 and again in 2006 when she was awarded a DBE. This appeared to formally signify a break with her punk roots. Yet Westwood had one punk tactic up her sleeve—or rather, her skirt. She arrived in Buckingham Palace to receive her OBE attired in a grey dress, the skirt of which cunningly hid the fact she was not wearing underwear. Various news outlets hailed this as a ‘punk twist’ on her otherwise sensible ensemble. But is punk standing in a palace amongst royals and nobles with no pants on? Or is punk standing outside the gates and throwing bricks at its walls?

https://wwd.com/eye/scoops/vivienne-westwood-obe-dress-no-underwear-queen-elizabeth-1235458358/

Westwood’s later collections became increasingly extravagant and regal, with images from artworks in London’s Wallace Collection—a museum of 18th-century treasures bequeathed by Sir Richard Wallace and the Marquesses of Hertford—printed on corsets and bodies utterly smothered with pearls. Dripping in frothy fabric, these outfits could have been pulled off the rails of a period drama set in the 1750s.

The most outrageous example of 18th-century opulence is arguably the ‘Madame Pompadour’ gown from the 1995-6 Vive La Cocotte collection—a dress so intensely aristocratic it would hardly feel out of place on a headless body in Revolutionary France. The gown is made from pale pink and shimmering blue fabric, ruched and ruffled into a tight bodice with a ballooning skirt and tight sleeves that burst forth at the ends, creating a waterfall of fabric down the arms. The five purple bows descending the bodice are so plump that they fight for space in the cinched waist. It is a stunning dress, plucked straight from the dreams of a girl who has just read Cinderella, and exudes naivety—or perhaps wilful ignorance—to the exploitation of the workers and slaves who fed the wealth of the 18th-century aristocrats and made such sumptuous attire possible.

https://www.instagram.com/p/Cues1FtSmVu/

Some might say the ‘Madame Pompadour’ gown is a performance, a dress designed to keep your attention on the superficial aspects of the monarchy—how they look and what they wear. Or perhaps the lavishness of the dress is parodic, ironising the obscenity of the wealth of the ruling classes. But when you sell clothes for thousands of pounds and sit in circles high above the heads of the average person, where the title ‘Dame’ might as well be ‘Queen’, the lines between tongue-in-cheek social commentary and reality become increasingly blurred.

Westwood was not anti-establishment. But she was, I believe, anti-mainstream. The various iterations of her World’s End shop, her movement away from punk when it became too popular, and her interactions with the royals and aristocratic iconography all point towards an unwillingness to settle and a desire to move in a small circle of her own, set apart from the crowd. Her orb encloses her world, and, together with the expensive price tag of her clothes, it remains hard for the masses to get close to her bright, creative genius.

References

Fury, Alexander, with Andreas Kronthaler and Vivienne Westwood.Vivienne Westwood Catwalk: The Complete Collections. London: Thames and Hudson, 2021.

Kelly, Ian and Vivienne Westwood. Vivienne Westwood. London: Picador, 2014.

Wilcox, Claire. Vivienne Westwood. London: V&A Publishing, 2004.