By Céline Rémont-Ospina

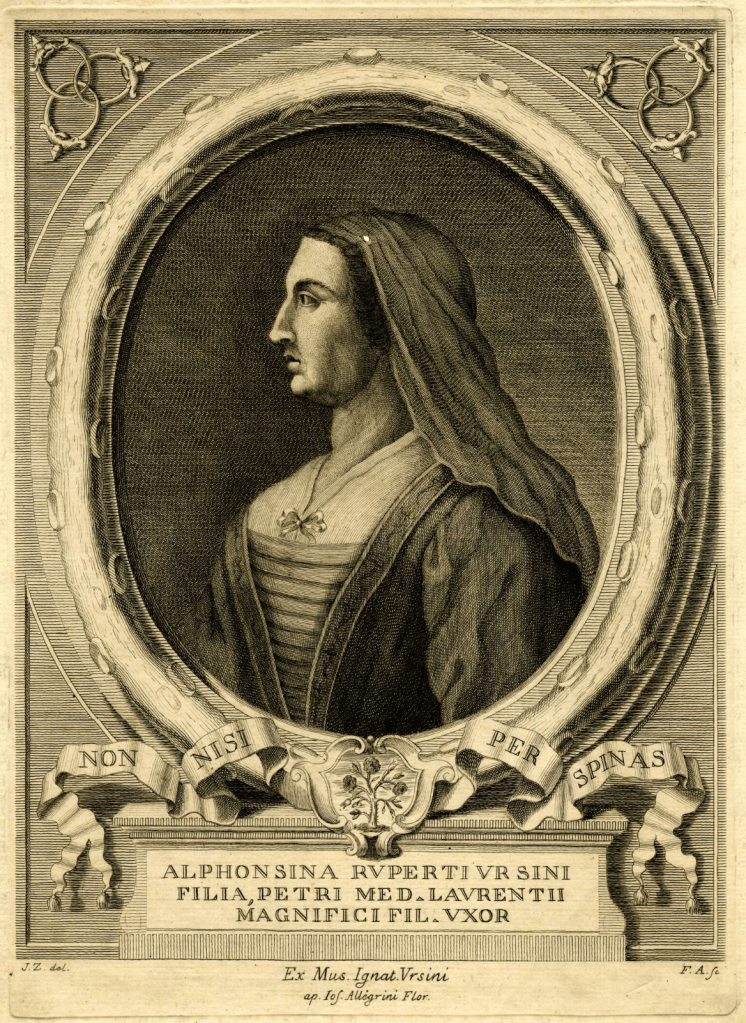

Born in 1472, Italian noblewoman Alfonsina Orsini (1472-1520) was raised in the royal court of Naples, a vibrant cultural centre during the Renaissance. Her father, Count Roberto Orsini, was a close ally of Ferrante, King of Naples. Following her father’s premature death, the young Alfonsina was brought up by her wealthy mother and her powerful uncle, who maintained close links with Ferrante. The sixteen years that this singularissima donna—or ‘most singular woman’ as one sixteenth-century biographer named her—spent in Naples proved foundational to her subsequent activities as a patron; first as a young spouse in Florence, and later as a widow in Rome, Florence, and the Tuscan countryside.

The court Alfonsina grew up in regarded cultural patronage and politics as two sides of the same coin – an attitude that effected the way she engaged with art. From a young age, she observed how Ferrante surrounded himself with a circle of artists and humanists to consolidate his political influence and further new objectives. Equally important was the place of noblewomen in the Neapolitan court at this time. Women like Alfonsina had unique access to positions of power and even the throne, giving them considerable leeway to commission art and architecture. More well-known contemporaries, like Isabella d’Este and her mother Eleonora of Naples (Ferrante’s daughter), would have undoubtedly served as powerful role models to Alfonsina in the Neapolitan tradition of creative female patronage.

https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/P_1871-1209-1191

At sixteen, Alfonsina married Piero de’ Medici (1472-1503), eldest son of the ruler of Florence, Lorenzo the Magnificent. This alliance was designed to enhance Medici’s status and strengthen the family’s bonds with Naples. Alfonsina’s substantial wealth enabled her to participate in her first recorded patronage activities. Alongside her mother and mother-in-law, she funded building works for a Florentine convent, securing private rooms for herself. Charitable activity like this was traditionally acceptable.

But Alfonsina soon ventured beyond conventional forms of female patronage: according to the sixteenth-century artist and writer Giorgio Vasari, she became the ‘first protector’ of the Florentine painter Mariotto Albertinelli, independently commissioning several (now lost) portraits that she sent to relatives in Rome. Directly supporting an artist in this way was unusual for a Medici woman and reflected the influence of the Neapolitan court.

Alfonsina’s life changed dramatically in 1494 when, only two years after her husband Piero’s accession to power, his poor political judgement triggered a popular uprising that drove the Medici family from Florence. Over the next eighteen years she endured the failure of Piero’s attempted returns to the city, his drowning in the Garigliano River, and the confiscation of Medici property, including Alfonsina’s own dowry. Newly widowed, she settled in Rome with her brother-in-law, Cardinal Giovanni de’ Medici, and the two exiles dedicated their energy to gathering support for their restoration in Florence.

In 1509, Alfonsina purchased the current-day Palazzo Madama from Giovanni, partly to relieve his debts, signifying the power afforded to her by her wealth. With the restoration of the Medici in 1512 to the leadership of Florence and Giovanni’s accession to the papacy a year later, the noblewoman saw a bright future for herself, her daughter Clarice, and above all her son Lorenzo, the focus of her social ambitions.

She commissioned the renowned architect Giuliano da Sangallo to design a grand new palace in Rome but the plans proved too ambitious. Instead, Alfonsina had her own residence built nearby (the present-day Palazzo Lante-Medici) of which only the ground floor survives. Her decorative programme includes the Orsini rose and the Medici six-ball coat of arms, symbolising the alliance of the two families. The integration of Alfonsina’s scudo accollato – a married woman’s coat of arms divided vertically into two parts, representing the emblems of her father and husband – celebrates her dual identity and dynastic power.

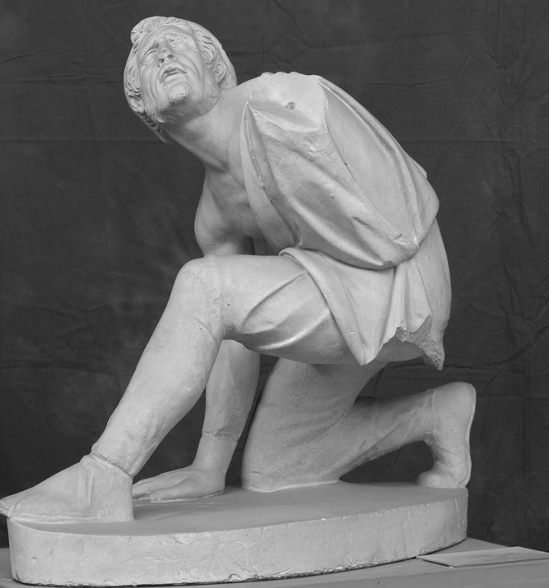

Alfonsina’s eye for art and strategic acumen are further demonstrated in her only recorded acquisition of Roman antiquities. She purchased a statuary group depicting fighting or dying men which was erroneously thought to represent the legendary Horatiiand the Curiatii (until modern historians found they replicated the Lesser Attalid Dedication group) and had been recently excavated in a Roman nunnery. The Roman legend served as a powerful illustration that one’s duty to the state should outweigh personal or family loyalties. Yet far from the ‘insatiable desire for antiquities’ displayed by her contemporary Isabella d’Este, Alfonsina soon separated the group as she saw in the acquisition an opportunity to nurture a crucial relationship for herself and her son, recently made ruler of Florence.

She sent the statue interpreted as the only survivor and victor of the group to her brother-in-law, Pope Leo X, most likely to celebrate his recent military and political successes. But beyond mere political manoeuvres, Alfonsina’s acquisition and display of the group made a long-lasting impression on artistic spheres. Perhaps the most important appropriations are found in Raphael’s cartoons for the Vatican tapestries and his Transfiguration, revealing the widow’s impact on visual culture in Renaissance Italy.

The following year, as Alfonsina’s son Lorenzo left to fight the French in Lombardy, she returned to Florence and began ruling in his stead. In a rather extraordinary move, Pope Leo X formally appointed her to organise his grand ceremonial entry into the city, praising her ‘strength of mind and of spirit’ which placed her ‘above the common condition of [her] sex’. Alfonsina oversaw the creation of a lavish programme of ephemeral decorations. This included the embellishment of church spaces, and along the procession, a series of triumphal arches, obelisks, statues, and paintings celebrating both the Pope and the Medici.

Her letters reveal her conservative aesthetic inclinations, impatience with the progress of plans (governmental bodies ‘spend [money] unwillingly’), and impressive leadership (‘nothing can be done unless I resolve it’). Her role and authority were unprecedented for a Medici woman, and did not go unnoticed: the population was largely outraged by the expenditure, and a satirical epigram specifically targeted Alfonsina: ‘O Florence, after this you have lost your liberty, for the woman of Orsini blood rules you alone.’

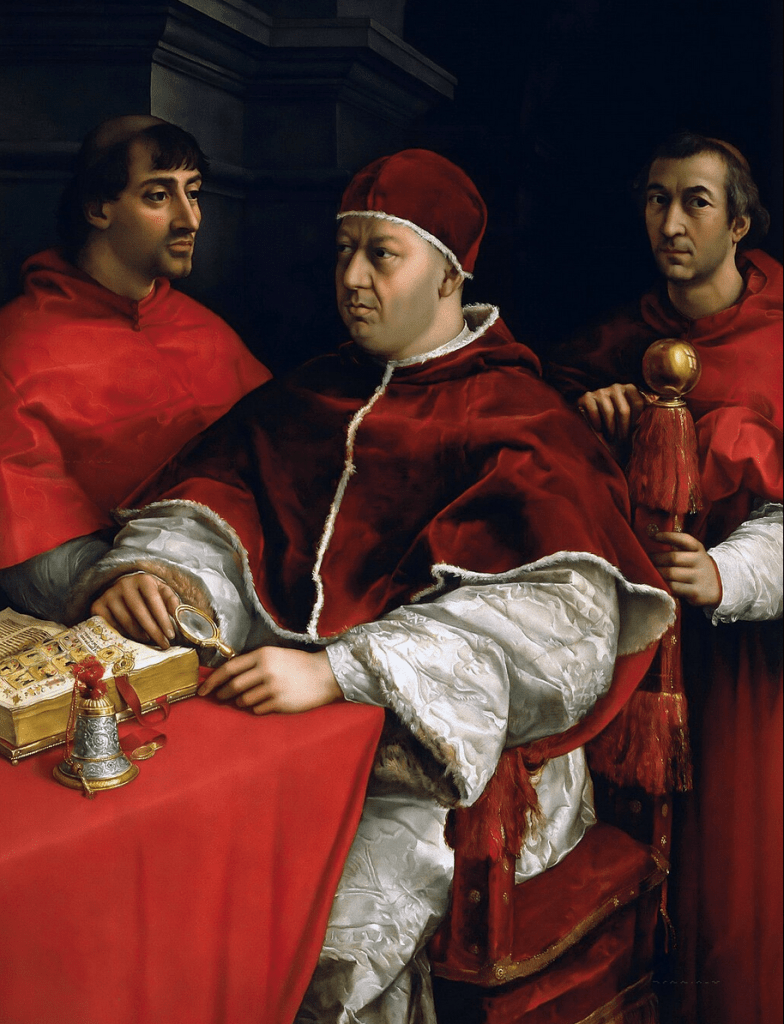

Slander aside, Alfonsina’s successful handling of the Pope’s ceremony seems to have facilitated her involvement in important building projects for the Medici, notably in Lorenzo the Magnificent’s sculpture garden and his villa at Poggio a Caiano, where her letters state she accomplished ‘a great deal of work and embellishment’. It is likely that Alfonsina and the Pope thought that the estate would host her son, the leader of the Florentine regime, and his new bride. Their wedding was celebrated there in September 1518; and true to form, Alfonsina commissioned lavish adornments, as well as musical and theatrical performances. She also had Raphael’s Leo X with Two Cardinals hung above the bridal table, a choice which, as she whimsically remarked, ‘brightened everything up’.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Portrait_of_Leo_X

Tragedy struck in spring 1519 when Lorenzo and his wife died within weeks of each other, leaving their infant daughter Catherine de’ Medici (1519-1589) – the future Queen of France – in the care of an ailing Alfonsina. This series of dramatic events was a turning point in the noblewoman’s political ambitions and patronage. Alfonsina had been able to become involved in political affairs and patronage processes not only because she had considerable financial resources and influential social contacts, but also because she could legitimise her ambitions by channelling them through her family, above all her son. His passing severely undermined her legitimacy and authority, and therefore her ability to manipulate Florentine political structures and participate in major cultural projects. Alfonsina died shortly after returning to Rome on 7 February 1520.

An impressive body of evidence records Alfonsina’s patronage. So how can we explain her historical invisibility and the dearth of scholarly publications on her contributions to the visual culture of Renaissance Italy? The extent to which her male relatives – the Pope, Lorenzo and Piero – overshadowed her may be part of the answer. Remarkably, she is absent from Giorgio Vasari’s fresco commemorating Leo X’s entry in Florence, despite her decisive role in the ceremony.

Furthermore, unlike the conventional patronage of other Medici women, Alfonsina’s bold political machinations, substantial wealth, (alleged) love of money and costly patronage were perceived as outrageous by contemporary chroniclers. Her own son-in-law jested that her burial was ‘most pleasant and salubrious to mankind’. Perhaps the subsequent Medici rulers refused to commemorate a Neapolitan-born Orsini widow who threatened behavioural norms for women. There is also the fact that no contemporary portrait of her survived, at least one that may be securely identified.

Her negative reputation has continued throughout the ages, with twentieth-century scholarship – probably following contemporary historians – portraying her as greedy and despicable. Alfonsina was certainly capable of manipulating her surroundings, and without her status or wealth she may never have achieved anything; but the same could be said of her male relatives who, in contrast, have remained prominent figures in cultural memory. The case of Alfonsina Orsini, in turn, reveals the significance and diversity of women’s patronage in Renaissance Italy, and the importance of shedding light on their powerful contributions to art and political history.

References

McIver, Katherine A., and Cynthia Stollhans, Patronage, Gender and the Arts in Early Modern Italy: Essays in Honor of Carolyn Valone. New York: Italica Press, 2015.

Reiss, Sheryl E., ‘Widow, Mother, Patron of Art: Alfonsina Orsini de’ Medici’, in Beyond Isabella: Secular Women Patrons of Art in Renaissance Italy, ed. Sheryl E. Reiss and David G. Wilkins, pp.125-157. Kirksville: Truman State University Press, 2001.

Solum, Stefanie, ‘Attributing Influence: The Problem of Female Patronage in Fifteenth-Century Florence’, The Art Bulletin 90:1 (2008), pp.76-100.

Tomas, Natalie, The Medici Women: Gender and Power in Renaissance Florence. Aldershot: Ashgate, 2003.