By Cosima Yeo

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig-tree in the story.

From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future

beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and

children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant

professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig

was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin

and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and

offbeat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and

beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out.

I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig-tree, starving to death, just

because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I

wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the

rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go

black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

Often quoted, and often uninterrogated, Sylvia Plath’s allegory of the fig tree in her 1963 semi-

autobiographical novel The Bell Jar has captured the imagination of a generation. This image of the fig tree has become central to discourse surrounding the female experience, expressing a sense of paralysis in the face of all of these seemingly mutually-exclusive futures. Yet, the fig tree as I interpret it is not emblematic merely of indecision, but rather it gestures towards the unresolved tension at the very core of Plath’s life and works, a tension she struggled with persistently and increasingly desperately.

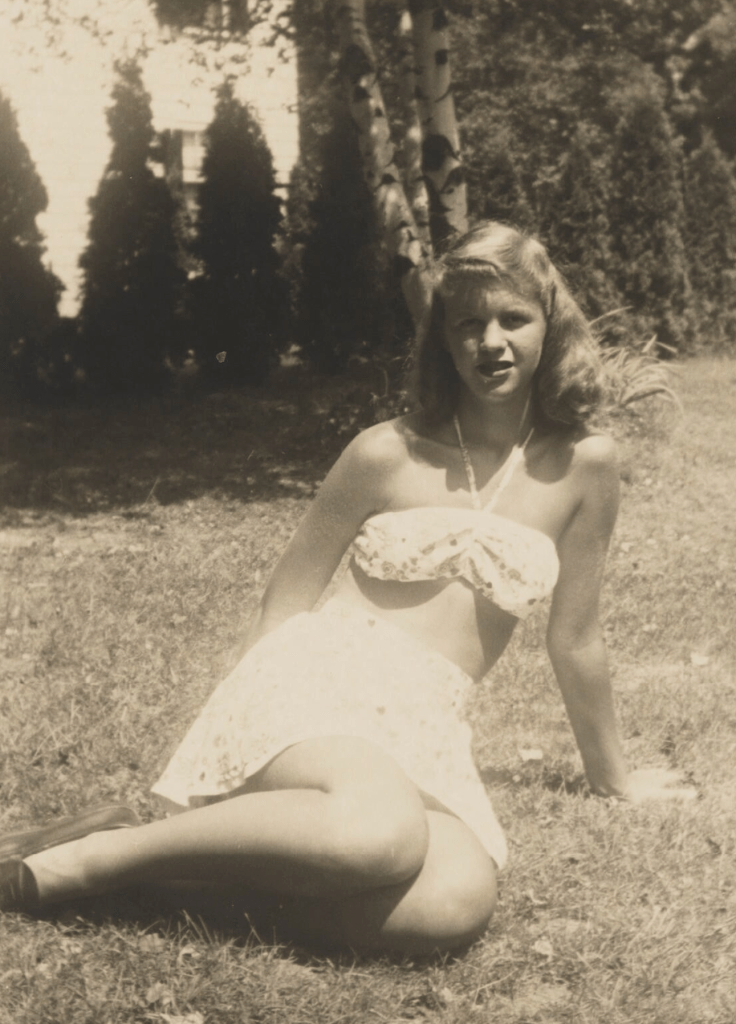

NPG P2013 © reserved; collection National Portrait Gallery, Londonhttps://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw270580/Sylvia-Plath?LinkID=mp81813&role=sit&rNo=1

In Plath’s novel, the protagonist Esther is torn between various alternative futures, a

multiplicity which seems to stifle rather than inspire her. Most crucially, Esther is caught

between what she sees as two conflicting choices: becoming a writer, and becoming a wife

and mother. Critical to the simile of the fig tree is a notion of binarism: to choose is to

forsake. Each fig represents a distinct identity, and when chosen excludes all others. This

double-bind seems central to The Bell Jar, as Esther manifests both a sense of abhorrence at

the thought of housewifery, and a compulsive need to adhere to societal expectations.

In the pages immediately preceding the fig tree allegory, Esther exhibits this compulsive

need to conform, as she spirals into self-doubt, enumerating a litany of perceived domestic

and intellectual shortcomings. Esther expresses an unease with the demands and

obligations of motherhood, stating “If I had to wait on a baby all day, I would go mad”. The

burden of possible pregnancy weighs heavily on her, as she states “A man doesn’t have a

worry in the world, while I’ve got a baby hanging over my head like a big stick, to keep me in

line”. Yet, elsewhere she expresses a longing for an idealised vision of motherhood,

imagining herself “dead white … but smiling and radiant” after childbirth. Plath thereby

encapsulates a strongly ambivalent attitude to pregnancy and motherhood, both a source of

revulsion and aspiration for Esther. However, the current day of Esther’s retrospective

narration, of which we only receive a glimpse, reveals that she does in fact have a baby. The

reader is left uncertain whether Esther is ‘healed’ and happy with her choices or not, an

ambiguity which I interpret as fundamental to the work.

This tension between Esther’s identities as a writer and as a wife and mother also seems

central to understanding Plath’s life and other works. Her journals reveal a fluctuating

attitude towards marriage and motherhood. Before meeting Ted Hughes, the accomplished

English nature poet whom she later encounters at Cambridge and goes on to marry, Plath

expresses a fear that “the sensuous haze of marriage will kill the desire to write”. Yet, Plath

does not seem to question whether she will marry and have children, but rather what effect

it will have on her:

Would marriage sap my creative energy […] … or would I achieve a fuller

expression in art as well as in the creation of children? …. Am I strong enough

to do both well? … That is the crux of the matter, and I hope to steel myself

for the test… as frightened as I am …

As her diaries progress, her attitude evolves, and she writes that:

My seventeen-year-old radical self would perhaps be horrified at this; but I

am becoming wiser, I hope. I accept the idea of a creative marriage now as I

never did before; I believe I could paint, write, and keep a home and husband

too.

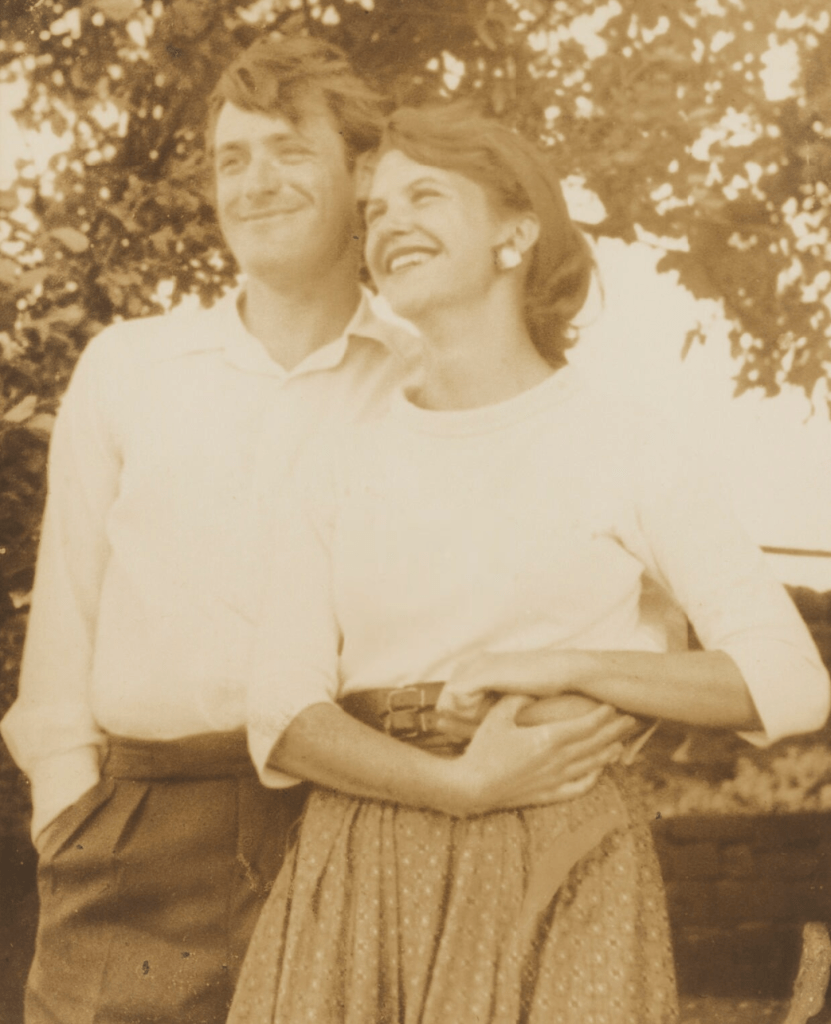

NPG P2012 © reserved; collection National Portrait Gallery, London.

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw270579/Ted-Hughes-Sylvia-Plath

Plath’s journals trace the evolution of her attitude towards marriage and motherhood,

culminating in a resolve to balance the conflicting needs of her creative ambitions and role

as a wife and mother. Yet, after the breakdown of Plath’s marriage with Hughes, largely due

to his infidelity, any sense of optimism collapses into poetic fury.

One such poem is ‘The Jailor’, which was originally written to be included in the Ariel (1965)

collection and then excised by Hughes when he edited and posthumously published Plath’s

The Collected Poems (1981). It begins with the forcefully visceral image “My night sweats

grease his breakfast plate”. Plath depicts a marriage which was stifling, founded on her fear

and subservience. Plath uses the language of sexual assault in her assertion that “I have

been drugged and raped”. Thus, Plath’s marriage to Hughes appears to actualise her fear of

losing her creative voice in marriage. Critics view Plath’s Ariel poems, written in the rage and

rubble of her marriage, as her best poetic works, perhaps suggesting, as Plath herself does

in ‘Lady Lazarus’, that her poetic power comes from rising from the destruction of her

marriage: “Out of the ash / I rise with my red hair / And I eat men like air”.

Plath’s ambivalence towards motherhood, as expressed throughout her life and works,

reemerges in the Ariel poems, written after the birth of her two children, Frieda and

Nicholas. In ‘Morning Song’, awe and love for her child are contrasted with a feeling of

fragmentation and distance. The joyfully extravagant simile of “Love set you going like a fat

gold watch” is undercut by the sparsity of the phrase “We stand round blankly as walls”.

This flat language suggests Plath’s emotional numbness, and her fragmentary

disconnect from her child is further expressed in the tercet “I’m no more your mother /

Than the cloud that distills a mirror to reflect its own slow / Effacement at the wind’s hand”.

bromide print, 1959, NPG x137160

© Rosalie Thorne McKenna Foundation;

Courtesy Center for Creative

Photography, University of Arizona

Foundation

https://www.npg.org.uk/collections/search/portrait/mw233527/Sylvia-Plath-Ted-Hughes

To return to Plath’s analogy of the fig tree, we see how choice-making is inscribed into much

of her oeuvre, through which she interrogates identity and explores ambivalent feelings

towards female choice-making, echoed across the character arc of Esther in The Bell Jar,

Plath’s journals, and the Ariel poems. Esther’s paralysis “in the crotch of this fig-tree”

mirrors Plath’s own struggle to reconcile marriage, maternity and her aspirations as a writer.

In her journals, this tension gradually transitions from resistance into a form of

reconciliation, yet her later poetic works reveal an emergence of bitter anger following the

breakdown of her marriage, suggesting that Plath continued to feel that her inertia was

causing her figs to rot, her choices to dwindle.

In light of this, the promise of free choice offered by the fig tree seems illusory. This

paralysis in the face of choice, as depicted by Plath, has implications for third-wave

principles of choice feminism. What is framed as uninhibited choice obfuscates underlying

hierarchies, pressures, and implications. The image of the fig tree undermines the concept

of neutral choice: the figs all seem equally “fat” and “purple” and ripe, yet they wrinkle and

die “one by one”, revealing that they are not qualitatively the same. A false notion of

neutrality conceals structural factors which place some branches out of reach, and social

forces which deem some of the figs more desirable than others. Yet what seems most

salient about the image of the fig tree is not the multiplicity of options, but the quiet

erasure of possibilities, stemming from inertia.

Plath offers no definitive solution to the questions which she poses, yet the trajectory of her

life and writing suggests that she saw suicide as a tragic and final attempt to seek some kind

of solution. Thereby, the fig tree simile becomes more than merely a symbol of indecision,

but rather seeks to reveal that choice, particularly within the context of gender, is in no way

free or neutral. It further reflects the stifling horror of being suspended between conflicting

identities and choices. Plath’s life and works compel us, then, to reconsider the idealised

emphasis that modern third-wave feminism places on the notion of individual choice.

Plath’s works resist simplicity. Instead, they operate within a space of ambivalence,

revealing the complexities of a truly free or ‘good’ choice.

References

Kukil, Karen (ed.). The Unabridged Journals of Sylvia Plath. New York: Anchor Books, 2000.

Plath, Sylvia. The Bell Jar. London: Faber & Faber, 1963.

Séllei, Nóra. “The Fig Tree and the Black Patent Leather Shoes: The Body and its

Representation in Sylvia Plath’s ‘The Bell Jar.’” Hungarian Journal of English and American

Studies, vol.9, no.2, 2003, pp.127–54.

Synder-Hall, R. Claire. “Third-Wave Feminism and the Defense of “Choice”.” Perspectives on

Politics, vol.8, no.1, 2010, pp.255-261.

Van Dyne, Susan. Revising Life: Sylvia Plath’s Ariel Poems. Chapel Hill: University of North

Carolina Press, 1993.