By Francesca Lamberti

“From a woman, sin had its beginning, and because of her we all die.” Here Ecclesiasticus 25:33 pithily encapsulates the Judeo-Christian curse of the daughters of Eve: women, descendants of the original sinning body, are bound to the myth of the Fall. When the serpent convinced Eve to take a bite from the apple, Woman betrayed herself as weaker, more easily tempted; in her influence upon Adam, Woman became the corrupter. The original sin was a carnal experience in the consumption of fruit, and thus the body of Woman, both easily tempted and tempting, became the locus of male fears about sex, gender, and power.

The myth of the Fall did not emerge from a vacuum: the anonymous author(s) of Genesis reflected their existent fears and ideas about Man and Woman in their writing. Over time, the circulation and canonisation of the tale crystallised these ideas into a convenient allegory, influencing, perpetuating, and justifying hierarchical structures that persist even today.

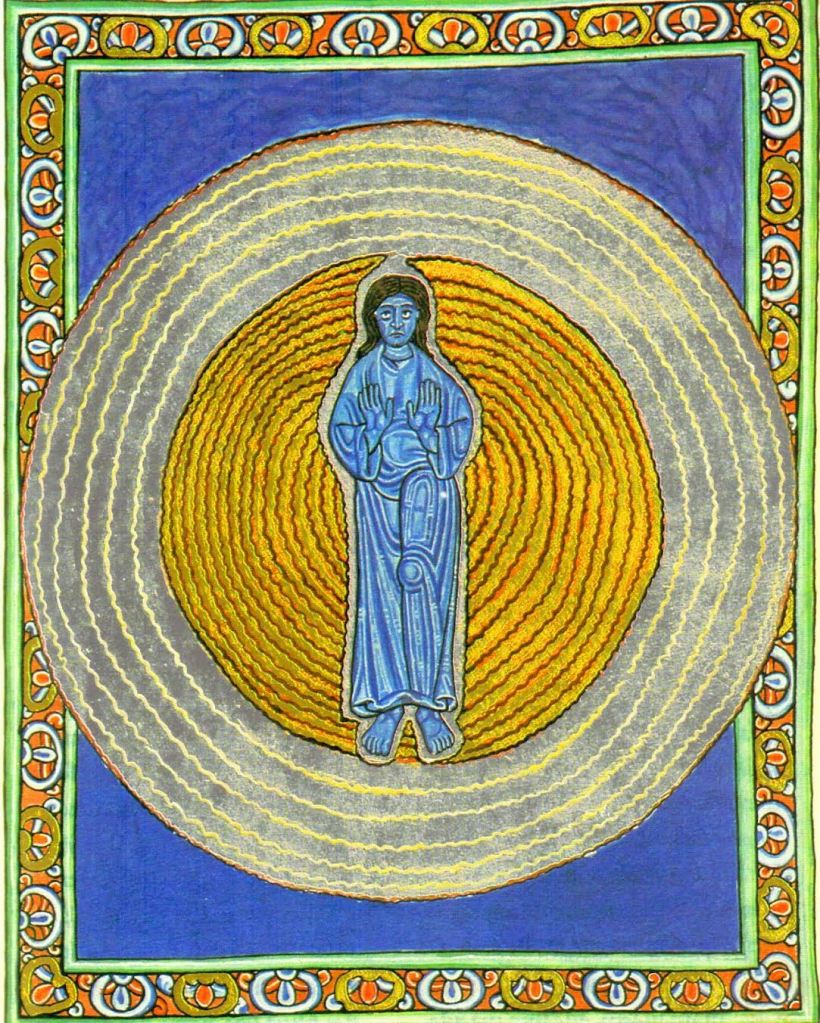

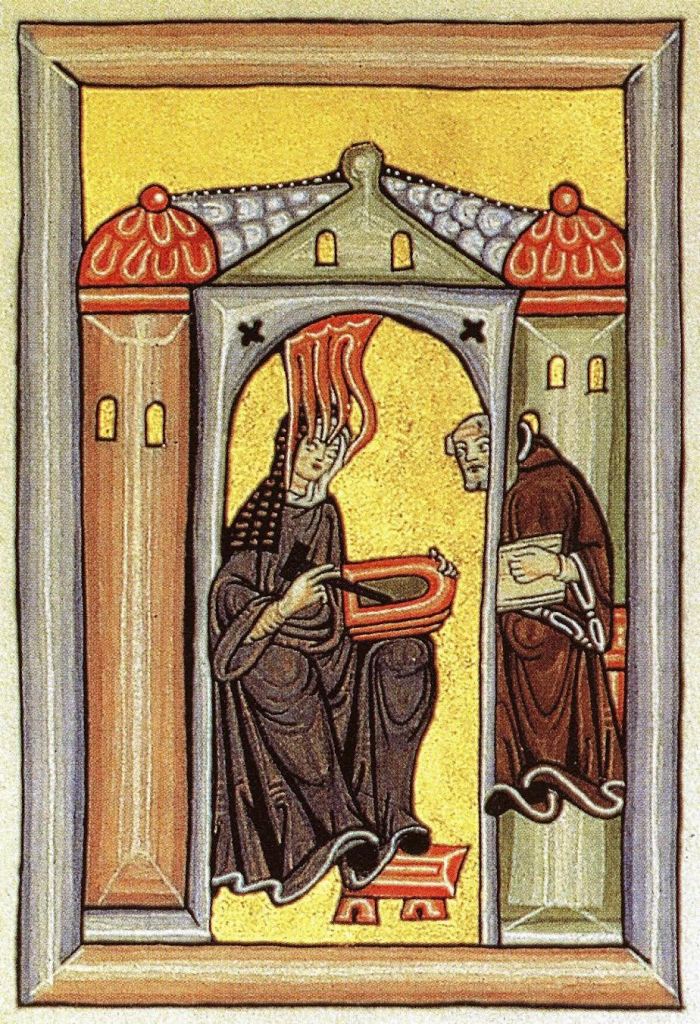

There are relatively few surviving texts by medieval women. According to historian Diarmaid MacCulloch, the intellectual centre of Latin Christendom had previously been nunneries and monasteries. However, the growth of female-excluding universities in the 12th century further alienated women from intellectual circles. Nonetheless, the texts that do survive by medieval women illustrate their continued contributions to theological discussions which were largely by men and for men. Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1172), a German polymath and abbess whose life traversed most of the 12th century, gained prominence even in her lifetime for her writings on theology, religious visions, poetry, and medicine. Much of her writing focuses on the figures of both Mary and Eve, creating a radical shift toward a more positive conception of Woman.

In the Scivias, completed c.1151, Hildegard subtly reinterprets the Fall by shifting attention to the role of the Devil. Medievalist Barbara Newman asserts that Hildegard consistently and forcefully assigns blame to Satan, presenting Eve as “more sinned against than sinning, [and] not so much tempted as victimised outright.” This framing shifts away from the trope of Eve as a sinning temptress by painting her as an unfortunate victim. It should be noted that this interpretation is in no way a complete subversion: Hildegard does not reject the opposition of Mary as the Holy Virgin and Eve as the Fallen Woman, as she continues to venerate virginity and virginal bodies as undoing the disorder caused by the Fall. Her image of Eve as a helpless victim raises concerns about notions of female agency, but to focus on this aspect may be to negate the crucial element that can be read in Hildegard’s Eve: a shifting of the blame from Woman to Satan which, though incredibly subtle, has significant consequences. In the Scivias, the Woman is not the original sinner but the original victim of sin; she is less the corrupter than the corrupted; and thus, the disparity in the blame between Adam and Eve shrinks.

Hildegard continues to reconceptualise Eve across her writings. Particularly significant is her lexical choice when referring to Eve in the Symphoniae (devotional chants). Scholars Lauren Cole and Hannah Victoria note that Hildegard refers to Eve only as femina rather than feminea forma (feminine form – the female body), in contrast to her lexical choice for Mary. This careful distinction, they argue, deliberately disassociates Eve from the image of the female body.

Taking this line of interpretation suggests that Hildegard’s conceptualisation of Eve was quite radical, for the theological world in which she lived and thought was saturated with notions of Eve’s enduring guilt. Theologian Jean M. Higgins, illustrating the myth of “Eve as temptress,” surveys prominent theological thought, including from contemporaries of Hildegard such as Thomas Aquinas, and finds that Eve “tempted, beguiled, lured, corrupted, persuaded…and thus became ‘the first temptress.’” Moreover, the Augustinian tradition with which Hildegard was deeply familiar links the body of Woman to her responsibility for the Fall: Augustine writes in his Literal Commentary on Genesis that “woman who was of small intelligence and who perhaps still lives more in accordance with the promptings of the inferior flesh than by the superior reason…through her the man became guilty of transgression.” Here Woman is body, and Man is reason; Woman sinned because of her tendency to follow the “promptings of the inferior flesh” and thus the body of Woman becomes mythologised as representative of temptation, seduction, and sin. By semantically distancing Eve from bodily existence, as well as focusing her blame upon Satan, Hildegard offers a subversion.

Hildegard’s views on sex, gender, and the body are highly complex. As one might note her significant reinterpretations of Eve, they must simultaneously acknowledge her many seeming contradictions. Barbara Newman notes that Hildegard “oscillated between a joyful affirmation of the world and the body and a melancholy horror of the flesh.” Her writings often centre women’s bodies and experiences, yet she “fully shared her culture’s notions of female inferiority.” However, to expect Hildegard’s work to be devoid of these complications is perhaps to misunderstand her historical context. The radicality of her writings, beyond the very fact of their existence, emerges in the subtleties: her focal shift toward women, her lexical choice in describing them, and her implicit lessening of their burden of guilt.

In Hildegard’s writings, we can see a 12th-century woman reinterpreting the foundational story that condemns her sex. In doing so, she contributes her voice to a patriarchal theological tradition, offering a perspective that quietly but radically posits a different fate for women.

References

Cole, Lauren, and Hannah Victoria. ‘Reorienting Disorientation: Hildegard von Bingen’s Depiction of the Female Body as Erotic, Fertile, and Holy’. In Medieval Mobilities, edited by Basil Arnould Price, Jane Bonsall, and Meagan Khoury, 49–75. Switzerland: Springer International Publishing AG, 2023.

Higgins, Jean M. ‘The Myth of Eve: The Temptress’. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 44, no. 4 (1976): 639–47.

Hildegard of Bingen. Selected Writings. Translated by Mark Atherton. London: Penguin, 2005

MacCulloch, Diarmaid. Lower than the Angels: A History of Sex and Christianity. London: Allen Lane, 2024.

Newman, Barbara. Sister of Wisdom: St. Hildegard’s Theology of the Feminine. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1987.