By Grace Hackett

If you’ve recently visited a museum with an antiquities section, you’ve probably passed by dozens upon dozens of black and orange pots without a second thought. They all look fairly similar, painted people in profile going about their ancient lives. It’s easy to dismiss them.

But you shouldn’t. The huge volume of vases that survive to the present are crucial to the study of the ancient world, particularly ancient Athens. Unlike the haughty literature of the educated, male elite, these pots lay in the dirt and avoided destruction in the changing world of Christianity. These vases show the raunchy sex, bawdy drinking parties, and crass humour that is rare in writing.

For centuries, these vases were studied in the same way until a method was developed by John Beazley, a professor at Lincoln College, Oxford to, as the theory goes, attribute certain vases to certain painters. This revolutionised the field. Gone were the days of viewing pottery as a vast and overwhelming corpus of works: vases were now viewed as products of individuals with artistic agency. Some of these once-known artisans are assigned names; others are known because they signed their works.

An example of a known painter is Dōris. Or Doris. Or Douris. So, in effect, a painter working at the start of the fifth century BC signed off on their vases with five letters: ΔΟΡΙΣ. This name can be transliterated in three ways due to the ambiguity of the letter omicron, ‘O’, in writing at this time, with different sounds and, as a result, different meanings. As Doris, it is male; as Douris, it is male; as Dōris, however, it is female. From the first time a scholar read this name, it has been taken for granted that this was Doris or Douris, usually Douris, but never Dōris. Since so many of these ancient potters and painters never left their signature, it has been taken for granted that they must have been male. Flicking through a handbook on Athenian pots, even those with unknown names are universally referred to as ‘he’ and ‘him’.

As previously discussed, writers from the classical world were overwhelmingly elite men who wrote about the sort of things that concerned elite men. These elite men were not concerned with women who were, for lack of a better term, ‘working class’, unless they could provide moral teaching or become a source of ridicule. If we believe the orators of the fourth century, women taking up work outside of their own household is, as R. Brock puts it, ‘degrading, embarrassing, and only acceptable as a temporary expedient under the compulsion of poverty.’ In the works of Aristophanes, women who worked in public, like the suggestive shopkeepers or foul-mouthed sellers in the marketplace, are a source of laughter. Respectable women were expected to be neither seen nor heard, staying in their homes except for in specific religious and ritual contexts.

But women did work. Throughout history, women who needed to work did so – and with dignity, even in the face of societal shame.

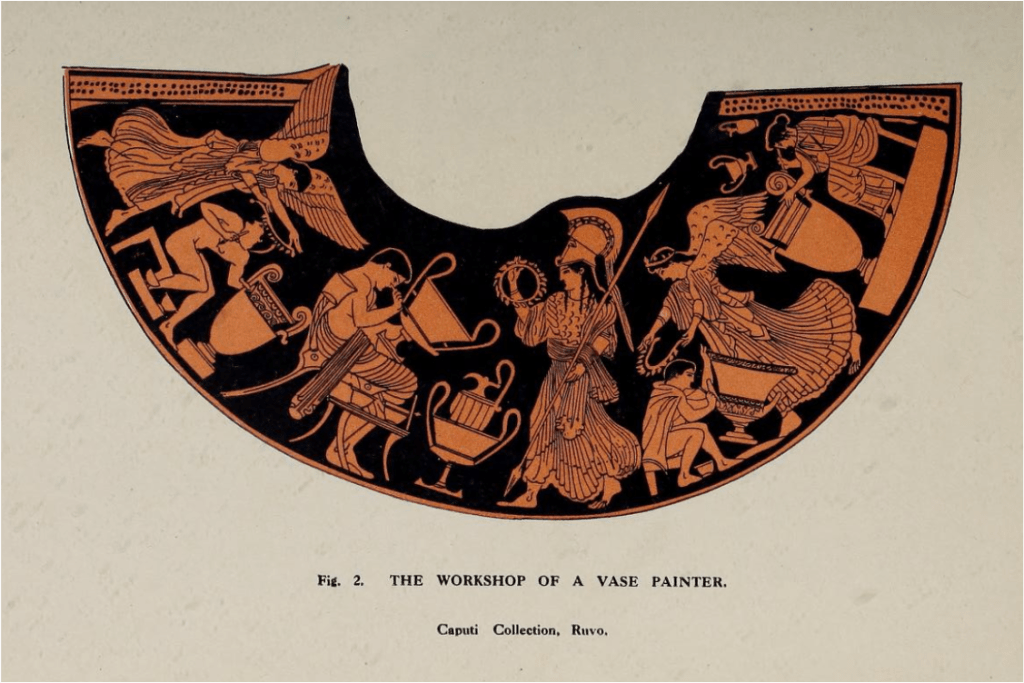

The evidence for women’s work in pottery is limited, but it does exist. A votive plaque from Corinth is usually interpreted as a woman working clay in her hands. A hydria from the fifth century BC in Vicenza, Italy, is the only surviving example of a woman working in a pottery workshop; it is called the Caputi hydria. It is decorated on its neck: four people are decorating pottery, but they are not alone. In the centre of the composition is Athena herself, armed and crowning the central workers with a garland. Two of the other workers, both male, are garlanded by winged nikai, winged personifications of victory. To the right, however, seated on a dais and decorating a colossal amphora, is a woman. Unlike the men, she is not celebrated by the mythical visitors. She just sits and works.

The general interpretation of the scene is that it depicts a successful workshop that had just won the commission to produce the Panathenaic amphorae, the large vases filled with olive oil that were given to prize-winners in the Panathenaic Games. The presence of the woman seems to be an afterthought, both to the painter and the modern academics who have studied it. The reason that she is not being crowned may be because she appears as a space-filler. And while these painted scenes are not photographs, such a casual inclusion of a woman makes it hard to believe that the painter would put her here without precedent somewhere. Perhaps he realised he had an empty space and, looking up from his vase in frustration, saw his female colleague working. Or perhaps the painter was a woman herself, making this a cheeky self-portrait.

Women did not produce the majority of pottery, they were not the majority of the wage-earning public, and if they did work it was largely viewed as shameful. But here is proof that women did work. On the Caputi hydria, the woman is probably not a salaried employee but a wife or daughter of the workshop owner, popping in to help out on a busy day in the shop; a busy day because of the recent Panathenaic commission. That is, when she wasn’t juggling children or spinning wool.

And this is one of the biggest problems about women’s work: most of it is gone. Women of ancient Athens completed a lot of domestic tasks, raising their own children, being paid to work as wet or dry nurses, or producing cloth for her household – which rarely survives in the archaeological record. The lost work of women is upsetting, but it is important to note that not all is lost. If women contributed to even 0.5% of the 133,533 vases in the Beazley Archive pottery database, then over six hundred examples survive to this day. These vases fill museums and collections across the globe, it is certain that a few vases, decorated by a woman’s hand, will be viewed lovingly by visitors all these years later. We may not know who they were, nor exactly what they produced, but we know they are there.

Feminist studies of Athenian pottery, though limited in numbers, do exist too. As a result, women are finally being considered as more active agents in vase creation. Mere decades ago, depictions of nude women were always assumed to show hetairai, sex workers employed for conversation and sex at the symposium. As a result, all nude paintings of women were considered erotic titillation for the men who bought them. This perception has changed. Women are now thought of as consumers of vases, either directly or through their husbands, suggesting that paintings on vases had some appeal to women. However, a more radical shift in feminist understanding of Athenian pottery only comes when we consider women not only as consumers, but also as creators.

References:

Brock, R., ‘The Labour of Women in Classical Athens’, in The Classical Quarterly 44.2 (1994), pgs. 336-346.

Kehrberg, I., ‘The Potter-Painter’s Wife: Some Additional Thoughts on the Caputi Hydria’, in Hephaistos 4 (1982), pgs. 25-35.

Lewis, S., The Athenian woman: an iconographic handbook (London and New York: Routledge, 2002).

Sparkes, B.A., The Red and the Black (London: Routledge, 1996).