By Olivia Hurton

Punchy, loud and readily available, Barbara Kruger makes art for an age that is, in her words, a ‘car crash of narcissism and voyeurism’. Her works engage the viewer through canny text and image combinations, appropriating the exhortative practices of advertising with a clear social purpose – to expose the underlying systems of power that dictate identity and use pervasive visual imagery as a means of coercion and control. As such, her subjects are power, violence, consumerism, class and sexuality, and the ways these are insidiously manipulated – so that receivers are rendered no more than a ‘reservoir of poses’, as the slogan runs on one of her 1983 works. For Kruger, image and language are always a reflection of political agenda; what is projected becomes society. Me becomes You.

Kruger credits her experience as a graphic designer as ‘the biggest influence on my work’. Early on in her career she was initiated into the world of glossy commercial publications by Marvin Israel, her tutor at Parsons School of Design and art director at Harper’s Bazaar. At twenty-two she headed for the doors of Condé Nast and was readily snapped up, installed in a room making small advertisements soon to become chief designer. Kruger explains that here she ‘learned to deal with an economy of image and text which beckoned and fixed the spectator’. She developed a keen awareness of what would become modern culture’s obsession with epigrammatic writing, ubiquitous in word-limited social media posts and captions. Kruger knew that for messaging to be effective in capturing attention-spans tested by the continual bombardment of adverts, televisions and magazines, it had to be impressionable at a glance. Images needed to be bold and simple; words needed to be clipped and direct.

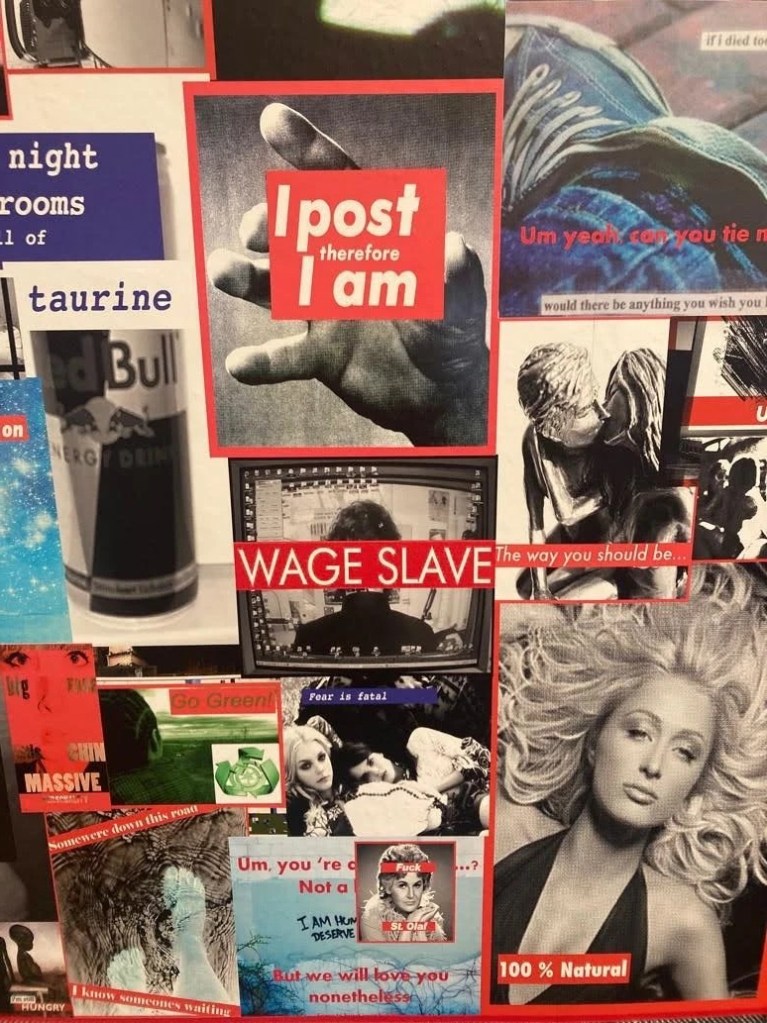

Transposing this to her artistic practice, Kruger developed an aggressive visual style. She culled monochrome images from vintage photography catalogues, instructional manuals and magazines, for their promotion of conservative social ideology and their stark aesthetic—an aspiration to clarity that reiterates Kruger’s desire for unambiguous political and artistic messaging, what she refers to as ‘cut[ting] through the grease’. On top of these she added strident verbal judgements lettered in white, red or black sans-serif fonts such as Futura Bold or Helvetica Ultra Compressed—a choice inspired by the eye-grabbing tabloid headlines of the New York Post, addressing her viewers with a sense of authority and urgency. It is often noted that Kruger’s work can seem jarring or confusing as word and image don’t always easily align, yet this is because her intention is to challenge the way we receive images. Her art disrupts to expose new perspectives by severing the relation between sign and signified, undermining the visual economy of power.

Kruger’s 2024 exhibition at the Serpentine, ‘Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You’, is an immersion into this world of dizzying discombobulation, of brazen information overload. In the South Gallery, Kruger presents works in her iconic photo-collage style. The walls are pasted with six large-format posters that collate parodic appropriations of her works mined from the corners of Tumblr, Instagram and Google Images. By turns pithy, ironic, and searingly truthful, this repository includes a sexy Paris Hilton still emblazoned with ‘100% natural’, a witty rejoinder to Descartes for the social media age (‘I post, therefore I am’), and a Hollywood pin-up tagged with ‘Makeup Makes The Heart Grow Fonder’. These displays powerfully convey the circular economy of imagery, the ways visual messages are continually ingested, appropriated and repurposed, for ends that purport to be trivial but which are, in fact, deeply political. Thus, divesting art of one of its central myths, Kruger suggests that the hand that constructs – or, more frequently, screenshots and edits – is always social.

Aware of technology’s power to influence and affront, Kruger extends her work to multi-media formats, masterfully employing video and audio. Walking through the gallery rooms, we are seduced by snippets of sound—‘Hello?’, ‘I love you’ and the kerching of the cash register—designating the exhibition space as one of enticement and confusion, as well as a place invariably implicated in the capitalist economics of exchange. As Kruger put it in a wryly self-conscious work from 1985, ‘When I hear the word culture I take out my checkbook’. Art can critique capitalism but remains a highly lucrative segment of it, a fact that Kruger exploits here for ironic play. In the North Gallery, Untitled (No Comment) showcases a mish-mash of video clips on a loop—a wry imitation of TikTok reels or YouTube shorts—standing as metaphors for the endless, cyclical nature of desire and history. As Kruger has observed, ‘nobody should be shocked by anything considering the histories of what we’ve done to one another. That’s true in terms of leaders; it’s true whether we believe or whether we doubt […] we see it acting over the centuries in so many ways’. Swept-up in a flurry of hair tutorial videos, circus acrobatics, talking cats and a sat-nav mapping the way to self-destruction, the thematic continuity of this series is only made apparent when text flashes onto the screen ventriloquizing Voltaire, ‘Those who make you believe absurdities can make you commit atrocities’, and Karl Kraus: ‘The secret of the demagogue is to make himself as stupid as his audience.’ For Kruger, the cat spouting politics is the buffoonish demagogue, just as the hair braiding tutorial, with its emphasis on the manipulation of physical appearance, stands for more insidious forms of social control.

‘Thinking of You, I Mean Me, I Mean You’ also explores the ways in which identity is shaped by space and reflects power relations. Growing up in a small room at her parents’ apartment in Newark, New Jersey, Kruger developed an eye for architecture and would compulsively sketch housing plans, envisaging places that would accommodate her mind’s vast perceptions. This exhibition demonstrates Kruger’s insights. Here space is used to subdue; many of the galleries are set up like pulpits, with benches facing towards towering screens exhorting political messages. On other occasions, space intimidates; in Untitled (Forever), her messages consume the viewer literally, as art extends over the floor, ceiling and walls. Flying in the face of the exclusivity and pretensions of the art world, Kruger makes her works hyper-available, whether through adverts pasted on taxis, t-shirts or, rather puckishly, in the Serpentine toilets. Speaking of her childhood, Kruger explains that she ‘never thought that art galleries and museums were for me’; in turn, her art now spills out into every space.

If Kruger’s art often feels like an assault, this is because it repudiates conventional systems of signs, it exposes our passive complicity in the fictions underpinning social formation, and it offers an onslaught of truths that fly at us as rapidly as social media stories – blink and you’ll miss it. Katy Hessel has written of Kruger’s ability to ‘bring meaning to often meaningless signage’. However, this misunderstands the basic premise of the artist’s philosophy: it is because signage is so fundamental in instilling the social directive and promoting stereotypes that Kruger seeks to raise the consciousness of her viewers. Be careful what you visually consume, she warns, you don’t know how it could be reshaping your identity, your values, and your desires. Before you know it, Me will become You.

References

Uta Grosenick (Ed.), Women Artists in the 20th and 21st Century (2005)

Katy Hessel, The Story of Art Without Men (2022)

Barbara Kruger, Remote Control: Power, Cultures, and the World of Appearances (1994)

Kate Linker, Love For Sale: The Words and Pictures of Barbara Kruger (1990)