By Helen Craske

“Un homme doit savoir braver l’opinion; une femme s’y soumettre” [Delphine]

(“A man must know how to defy opinion; a woman, how to obey it.”[1])

Madame de Staël has been called ‘one of the most important women in history’ (Bowman, in Dixon, 2009, p.9), and this is for her impact over politics, Romanticism and women’s writing. Flaubert considered her as influential, or even more so, than Voltaire, with whom a tempting comparison arises: both writers were hounded by political censorship and persecution, both held popular “salons” bringing together some of the greatest minds in Europe, and both supported “Enlightenment” ideals. However, Mme de Staël presided over a momentous transition, both political (she experienced the radicalism of Revolution, the disappointment of ideals during the “The Terror”, and the gradual rise of despotism under Napoleon) and literary: the movement towards Romanticism, from which literature of the 19th century was to develop. It is thus through her engagement with contemporary debates regarding: literature, the relationship between the Self and Society, and the role of women therein, that makes Germaine de Staël a truly “ground-breaking” woman.

Literature: Revolution and Romanticism

It was of no small significance that Staël, in De la littérature[2] (“On Literature”) (1800), called for ‘a revolution in literature and the arts’[3]. By using the language of revolution, she was making the literary political; an alignment that continues throughout both her theoretical and fictional works. This ‘revolution’ opposed the restrictions of “Classicism” or “good taste”, whose rigidity was, Staël argued, unnatural, in that France’s ‘social institutions, its social customs, had replaced natural affections’[4]. Such arguments are clearly influenced by Rousseau’s portrayal of the “state of nature” and of society as corrupting our freedom, equality and wellbeing as individuals. By making such a clear link between literary rules and social expectations, indeed – by equating them or making the former a product of the latter, Staël controversially questioned the role of social and, above all, political institutions over our experience of reality. Literary and political “despotism” were to be feared and rejected, and such views were swiftly suppressed; one particular phrase being too dangerous to pass censorship: ‘Good taste in literature is, in some respects, like order under tyranny; it is important to examine at what price it is bought.’[5] Literature must therefore be freed from the restraints regarding subject matter, form and expression that were imposed from above, and instead turn towards the individual “Self”.

This preoccupation with the experiences and feelings of the individual was to dominate “Romanticism” for years to come. Despite moving away from “Classical” rules, Staël sill justified the evocation of sentiment via traditional concepts of the arousal of pity and fear, in order to reach a catharsis serving “moral” aims. The main difference was the “level” of subject matter: the “everyday” experience of (in particular) the bourgeoisie was to exemplify “reality” of feeling, engaging the reader more fully and thus producing more effective results. Indeed, despite the later scorn “Realist” authors would show towards the “sentimental” fiction of Mme de Staël, she did in fact help pave the way for their own form of writing when she claimed that: ‘Novels which depict life as it is, with finesse, eloquence, depth and morality, would be the most useful of all genres of fiction’[6]. Thus feeling was to be seen as integral to the portrayal of reality, and feeling was ascribed, above all, to the “feminine”.

Sentiment and “sensibilité”: women in literature, women in society

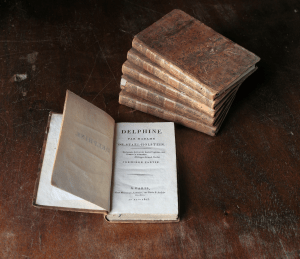

Staël’s portrayal of women in society, namely in her two novels, Delphine (1802) and Corinne, ou l’Italie (“Corinne, or Italy”) (1807), is one of a struggle of the (female) individual’s emotions against the overarching power of (patriarchal) social convention and expectations. The issue of personal as opposed to social “contentment” is therefore especially gendered[7]. Both Delphine and Corinne are placed in victimised roles due to their love for a man which transgresses social norms. They are at the mercy of the almost omnipresent “opinion” which defines acceptable behaviour. Delphine laments at the division in society between ‘the kindness of the heart’ and ‘the duties imposed by society’[8]; duties which are linguistically prescribed via the spoken and written judgements of “Others”. Here we see Staël’s views on the abuses inherent in the relationship between society and language being put into practice, in order to question the role enforced upon women in society. The plight of women in Staël’s texts, however, is a lost battle; Corinne is said to be fighting the very ‘nature of things’[9].

The fatalistic aspects of Staël’s novels are balanced, though, by their psychological insights and, in the case of Corinne ou l’Italie, the appraisal of the female intellectual. By aligning the heroine with her motherland, Staël attributes to Corinne the journey of discovery that Oswald, her love interest, undergoes in his travels to Italy. This can be interpreted as a search for the “Other” (see Vallois, 1987, p.131), which is experienced by each of the lovers, for both have a passion for another so different from themselves; Corinne’s free-mindedness juxtaposing Oswald’s conformism. Such a quasi-masochistic desire for a love with obstacles has underlying Freudian implications: Oswald’s transgression against his dead father’s wishes, in loving Corinne, having arguably Oedipal elements. Above all though, Oswald is surprised, attracted and yet also repulsed by the status of Corinne as a celebrated artist: as ‘a woman renowned for [her] gifts of genius alone’[10]. Her love for Oswald becomes self-sacrificing, and this is at the expense of her art. Staël thus demonstrates how social expectations prevent gifted women from pursuing happiness in love relationships, since the traditional role given to women is to be inferior to men. However, by demonstrating Corinne’s clear superiority to Oswald, Staël creates her female version of the Romantic hero; someone misunderstood and persecuted by society, such as would be explored in her later “De l’Allemagne” (“On Germany”): the‘Bible of Romanticism’(Dixon, 2007, p.10).

Madame de Staël: the legacy

Mme de Staël’s legacy lies in her application of Enlightenment ideals and Romantic sensibilities to the situation of women in society, as well as in her contributions to literary debate by insisting on the integral influence of social and political institutions, and by encouraging what we would now call “comparative literature”. Though she may have depicted the female situation as fatalistic, and not have gone beyond the traditional marriage structure, such criticisms are based on anachronistic extrapolations of 20th century feminist theory which, perhaps unfairly, underestimate the importance of Staël’s works. She helped to evolve the concept of the “Enlightenment” so that it involved women as much as men; opening the discourse which continues to this very day: what does it mean to be a female intellectual?

[1] All English translations of quotations from Mme de Staël’s texts will be my own.

[2] It’s full title being:De la littérature dans ses rapports avec les institutions sociales, or: “On Literature considered in its relations to Social Institutions”.

[3] ‘une revolution dans les lettres’ [De la littérature, Seconde partie, Chapitre 2].

[4] ‘ses institutions, ses habitudes sociales avaient pris la place des affections naturelles’ [Ibid].

[5] ‘Le bon goût en littérature est, à quelques égards, comme l’ordre sous le despotisme; il importe d’examiner à quel prix on l’achète.’ [De l’Allemagne, Seconde partie, chapitre XIV].

[6] ‘Les romans qui peindraient la vie telle qu’elle est, avec finesse, éloquence, profondeur et moralité, seraient les plus utiles de tous les genres de fictions.’ [Essai sur les fictions (1795)]

[7] For the groundbreaking text which highlighted so forcefully the divide between sex and gender, see De Beauvoir’s The Second Sex.

[8] ‘la bonté du coeur’ vs. ‘les devoirs imposes par la société’.

[9] ‘Elle avait à combattre la nature des choses.’.

[10] ‘une femme illustrée seulement pour les dons du génie’.

Further Reading:

Texts in English

Cohen, Margaret, “Women and fiction in the nineteenth century” in: Timothy Unwin (ed.) (1997) The Cambridge Companion to the French Novel: from 1800 to the present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Chapter 4].

Dixon, Sergine (2007) Germaine de Staël, Daughter of the Enlightenment: The Writer and her Turbulent Era. New York: Humanity Books.

Finch, Alison (2000) Women’s Writing in Nineteenth-Century France. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Chapter 4: ‘’Foremothers’ and Germaine de Staël’].

Goodden, Angelica (2000) Madame de Staël: Delphine and Corinne. London: Grant & Cutler Ltd.

Isbell, John Claiborne (1994) The Birth of European Romanticism: Truth and Propaganda in Staël’s ‘De l’Allemagne’, 1810-1813. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Texts in French

Staël, Madame de, and Georges Solovieff (ed.) (1974) Madame de Staël: Choix de textes thématique et actualité. Paris : Klincksieck [This invaluable text provides excerpts of Staël’s works under useful thematic headings].

Vallois, Marie-Claire (1987) Fictions féminines: Madame de Staël et les voix de la Sibylle.Saratoga, Cal : Anma Libri.