By Cameron Bowman

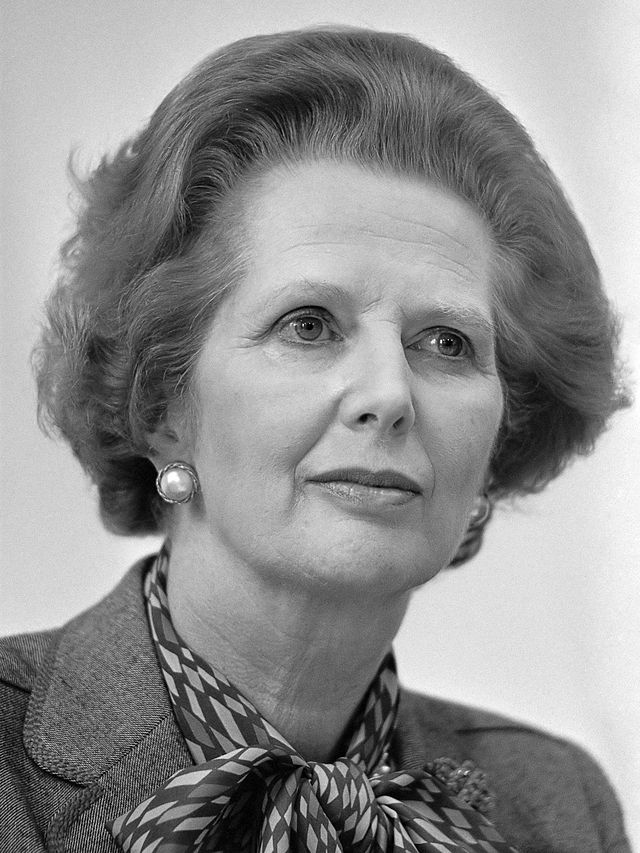

A term widely used in the humanities, coined by Thomas Kuhn, is ‘paradigm shift’. This occurs when established conventions are shattered by an innovative approach. In Britain, the turn to neoliberal politics and economics in the 1980s is often considered a paradigm shift: policies once considered unthinkable, including privatised energy and transport sectors, deregulated financial exchanges, and mass home ownership, are norms we live with today. As Margaret Thatcher was instrumental in implementing these policies in the UK, an assumption follows that Thatcherism and the ideology of neoliberalism are synonymous terms. This is due in part to Thatcher’s close personal relationship with one of the founding fathers of neoliberalism, the Austrian economist Friedrich Hayek. Thatcher, however, never merely parroted Hayek or Hayekian ideas. Instead, she effectively cherry-picked parts of Hayek’s rhetoric for her own purposes.

Thatcher maintained throughout her life that Hayek’s famous Road to Serfdom, which she read while an undergraduate at Oxford, had a profound impact on her thinking. Road to Serfdom is Hayek’s account of the fall of Weimar Germany, in which he argues that the introduction of democratic socialism—e.g. a planned economy where the people voted on the plan—would always lead towards totalitarian thinking, including the rise of National Socialism in Germany. According to Hayek, the state’s need to please the people would lead to increasing restrictions on the freedom of the people. In a planned economy the individual cannot, for example, start their own business or buy their own house; following a politician’s promise for universal social housing or 0% unemployment, the state takes care of that for them. The individual therefore comes to rely on the state and its promises as the only recourse for change. Economic paralysis of the Weimar state in the 1930s thus laid the foundations for the appeal of Hitler’s promises. Conservatives in 1945 were attracted to this claim as it laid the blame for the Second World War firmly at the foot of socialist ideology. Churchill’s campaign team incorporated ideas from Hayek’s Road to Serfdom in his 1945 election bid, leading him to the blundering claim that a vote for Labour was a vote to introduce the Gestapo to Britain. Churchill lost the election resoundingly.

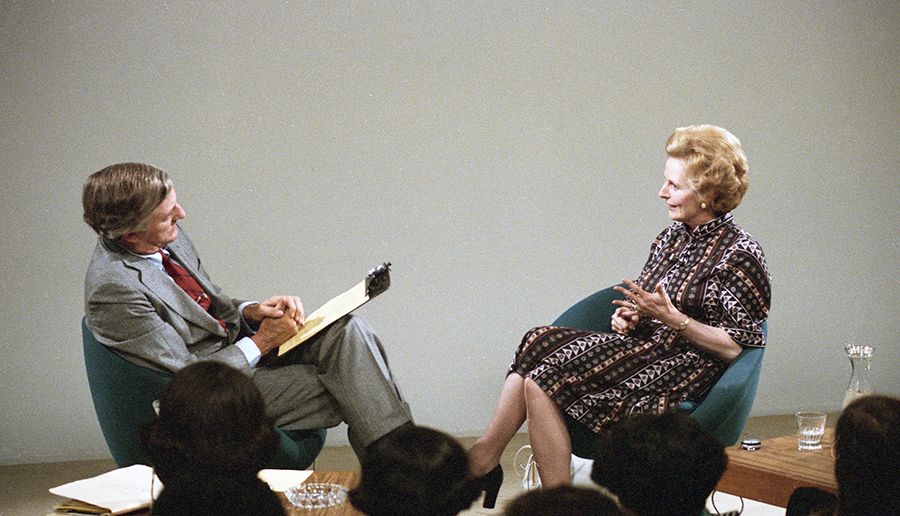

In the 1970s Hayek experienced a resurgence in popularity, and the Conservatives even ensured that Road to Serfdom got another run in the print with Routledge. During Thatcher’s time in opposition, some of her rhetoric was lifted, often word for word, from Road to Serfdom. In a dazzling interview for the American TV show William Buckley’s Firing Line, she effectively claimed that the experience of the 1970s, involving the three-day work week, mass strikes, and rocketing oil prices, was reminiscent of early 1930s Germany. Britain, in the hands of the socialists, was sliding away from being a free society, towards, as she ominously put it, ‘something else.’ Thatcher is often remembered as the Iron Lady, a woman of immense and immovable conviction. Her interview with William Buckley is worth watching to remind us that a part of her appeal was also a great deal of charm, a characteristic which clearly influenced the nation. She was the first leader in the age of mass franchise democracy to win three back-to-back elections.

Throughout her premiership Thatcher and Hayek maintained a close personal relationship, meeting regularly and exchanging letters. A clear benefit of their relationship, however, was that it offered some intellectual authority to Thatcher’s government rather than any key influence on policy. The demand for expediency when in power meant policies were often pragmatic and piecemeal in comparison to what Hayek proposed. Nonetheless, keeping a neoliberal ideologue around reminded everybody that this was a different, new-look Conservative party. In one famous and probably apocryphal incident, when frustrated with her cabinet’s indecisiveness during a meeting, Thatcher supposedly brandished a copy of Hayek’s other magnum-opus, The Constitution of Liberty, and declared ‘this is what we believe!’ There is little indication, however, that Thatcher ever actually read the much longer, denser, and more radical Constitution of Liberty.

This brings us to the major points of difference between Thatcher and Hayek: their faith in democratic institutions. Hayek’s Road to Serfdom left little room for antisemitism or indeed right-wing populism in his account of the rise of the Nazi party; instead, it was the combination of socialism and democracy that had led to National Socialism in Germany. Hayek became even more hardline in later years, declaring in 1981 that he preferred ‘a liberal dictator to democratic government lacking liberalism.’ Democracy, in Hayek’s eyes, puts too much power in the hands of the people. Hayek was famously very cosy with the Chilean dictator, Augusto Pinochet. When asked about Pinochet’s violent methods being akin to totalitarianism, he declared that the real totalitarian was Pinochet’s predecessor, Salvador Allende. Allende had, of course, been democratically elected.

An uneasiness about the sovereignty of the people was not a conviction that Thatcher shared. She admired Pinochet, once stating the policies of his dictatorship were a ‘striking example of economic reform from which we can learn many lessons.’ Thatcher, however, remained committed to democratic principles. In the now famous 1987 ‘no such thing as society’ interview, she also stated, ‘The whole essence of democracy is that you submit yourself to the people and it is from the people that your authority comes.’ Furthermore, in one letter Hayek encouraged Thatcher to imitate some of Pinochet’s more extreme (and presumably violent) methods to liberalise the economy; she replied, courteously stating, ‘I am sure you will agree that, in Britain with our democratic institutions and the need for a high degree of consent, some of the measures adopted in Chile are quite unacceptable.’

Hayek and Thatcher were often singing from the same hymn sheet. They were doing so, however, in markedly different chapels. What we see in Thatcher’s case is an ability to effectively pick and choose the most effective pieces of rhetoric and narrative from Friedrich Hayek: namely, his critique of socialism. This provided Thatcher with the intellectual authority required for her radical re-working of conservative politics, a re-working that has fundamentally changed how every successive government has thought about what is possible in British politics.

References

Hayek, Friedrich. The Road to Serfdom. London: Routledge Classics, 2001.

Margarat Thatcher Foundation. ‘Thatcher, Hayek and Friedman.’ Accessed February 26. https://www.margaretthatcher.org/archive/Hayek

Sutcliffe-Braithwaite, Florence. ‘Neo Liberalism and Morality in the Making of Thatcherite Social Policy.’ The Historical Journal 55, no 2 (2012): 497-520.

Farrent, Andrew. and McPhail, Edward. ‘Hayek, Thatcher, and the Muddle of the Middle,’ in Hayek: A Collective Biography, Vol IX: The Divine Right of the Free Market. Edited by Robert Leeson, 263-284. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.